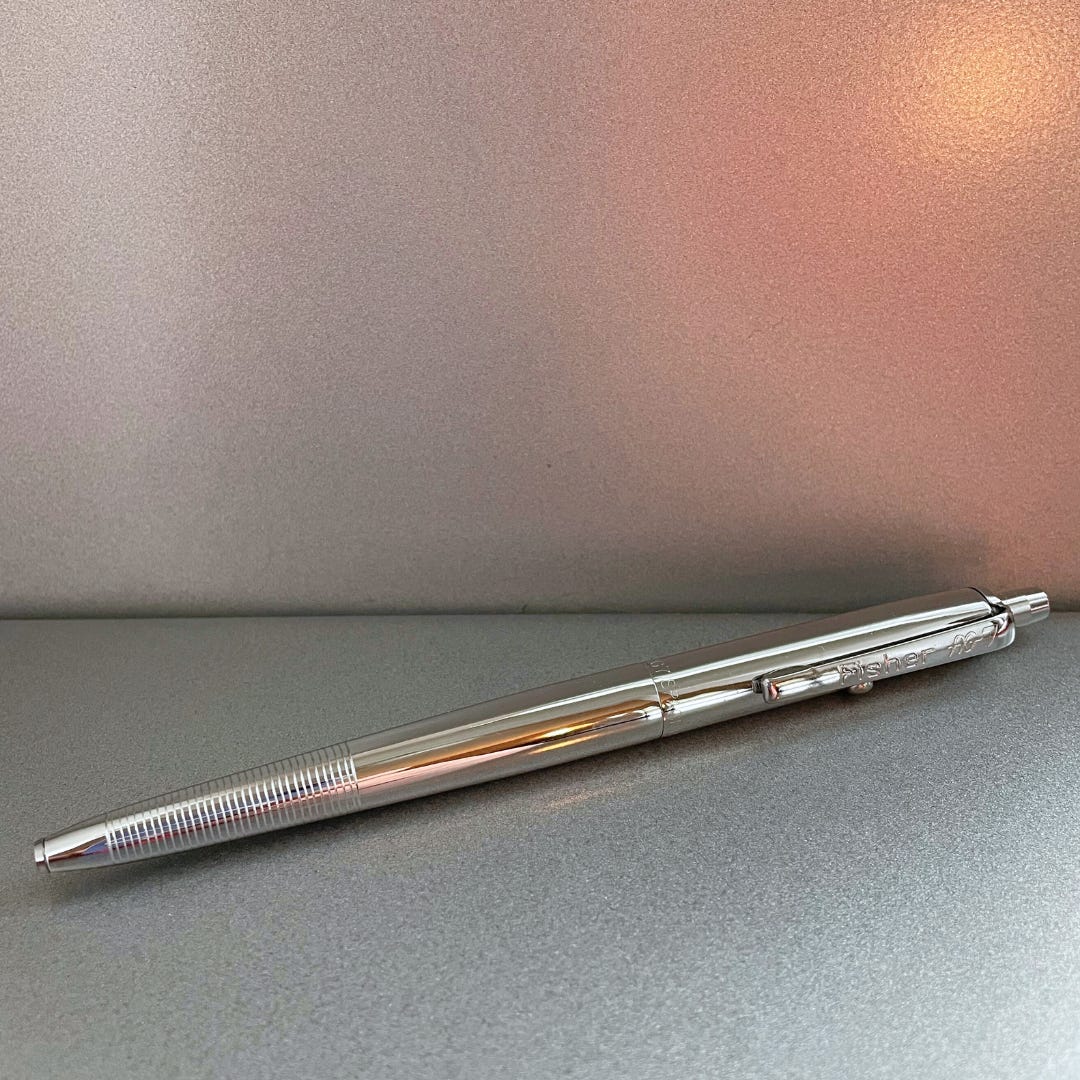

THE FISHER SPACE PEN

"I was my family’s first college graduate and didn’t have much confidence in my intellect, but the way Quang listened to what I had to say put me at ease from the start."

My father-in-law, Quang—Dad, as I called him—came to America in 1952 on an engineering scholarship and made a living teaching Vietnamese to D.C. diplomats.

When my then-boyfriend Vinh introduced us, at a showing of the Buddhist-leaning The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy, Quang and I talked about Thich Nhat Hanh, the celebrated Zen Buddhist monk whose books we’d both read and who, it turned out, Quang had gone to high school with. I was my family’s first college graduate and didn’t have much confidence in my intellect, but the way Quang listened to what I had to say put me at ease from the start.

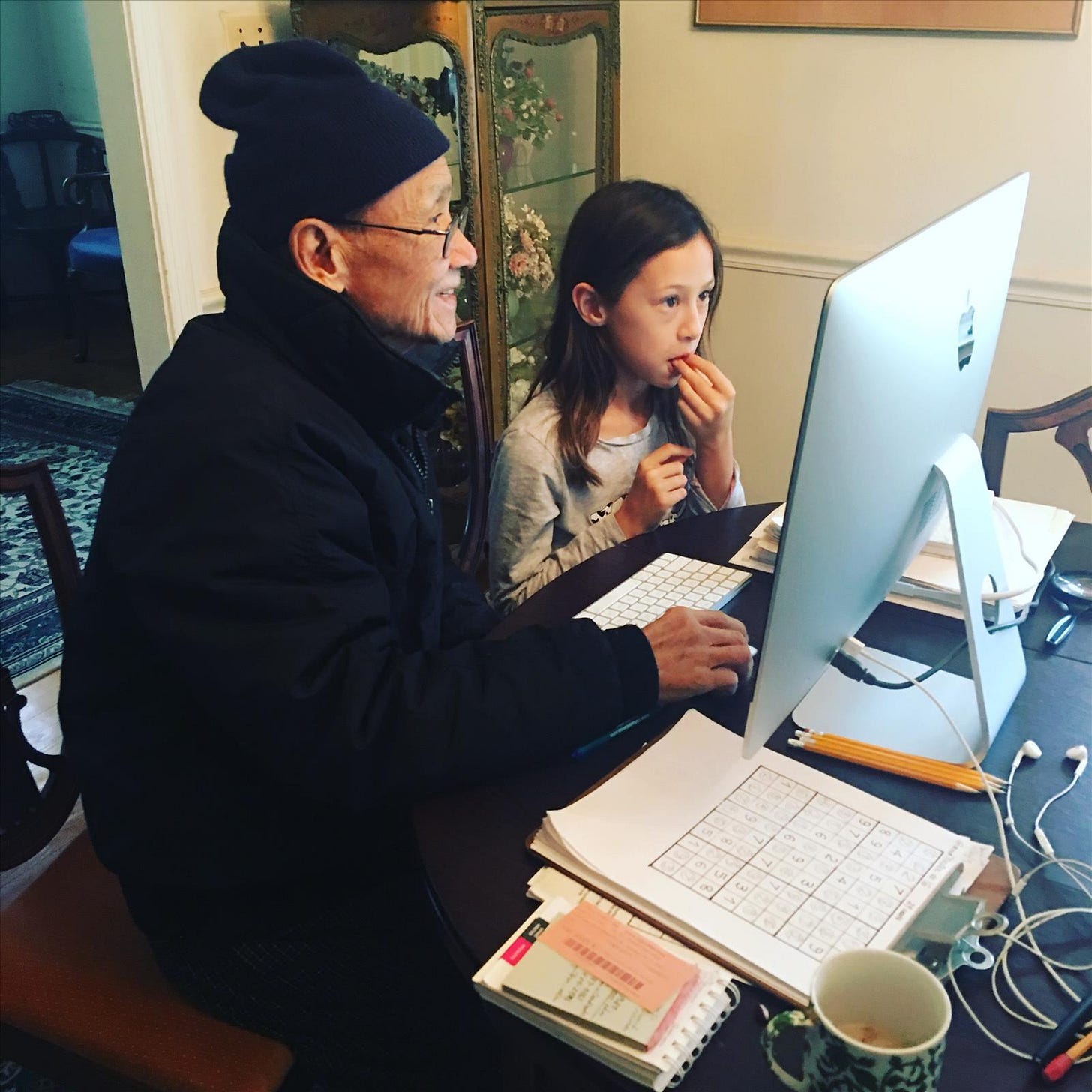

“What are you reading?” he always asked when Vinh and I visited. He taught me how to play sudoku. I introduced him to the documentaries My Architect and How to Cook Your Life. He gave me The China Study, which explored how eating vegan could help prevent chronic disease. I showed him how to make Mexican street corn.

Vinh and I got engaged. At the rehearsal dinner before our wedding, Dad raised his glass. “To Kristen, who knows more about Buddhism than any person I know.” He saw a person my own parents did not.

Dad had written an English-Vietnamese phrasebook. I wrote a memoir. He believed in me as a writer and a thinker. He fed my hunger for knowledge, stocking the guest room with books about the Heart Sutra, stacks of Tricycle magazine and back issues of The New Yorker. My cheap blue suitcase became a rolling library with a borrower of one.

“My ancestors were mandarins in the Imperial Court,” he said one day.

“What’s a mandarin?”

“A scholar.”

He adopted me as part of his erudite lineage, and I gratefully embraced my new place. We kept talking and learning, even when cancer interrupted our conversation. In the hospital, I showed him the app Ten Percent Happier. I played a guided meditation that eased him into sleep.

After Quang passed away, on December 11, 2019, Vinh gave me his Fisher Space Pen. I don’t know when or how Dad came to own the pen, but I know that astronauts used one just like it on the Apollo 7 mission in 1968. I imagine that as an engineer and lifelong tinkerer, Dad admired its ability to write in zero gravity, underwater, over grease and in extreme temperatures. I imagine that he imagined it traveling through space, floating, weightless despite its solid-brass heaviness, hitching a ride across the galaxy.

In death, Dad’s body traveled through space too, flying from Washington, D.C., to a cemetery near a Buddhist temple in Hue, Vietnam. I imagined the sound of bells floating over the quiet stones as monks in bright saffron robes lowered him to rest. Vinh and I used Google Earth to hover over the cemetery looking for him. Grief is heavy, but love is weightless. I think he’d be happy I have his pen.

—Kristen Paulson-Nguyen

Kristen Paulson-Nguyen’s graphic memoir To Have and to Hoard was an Editors’ Pick in Solstice’s 2023 Summer Contest Issue.

"Grief is heavy, but love is weightless." what a comfort to read this line. This was a beautiful piece to read and reflect on. I'm grateful to Grub Street for linking to it in a recent newsletter. Thank you, Kristen, for sharing the story of you and Dad with us.

This is gorgeous, Kristen