MOM'S TIME-OFF REQUEST

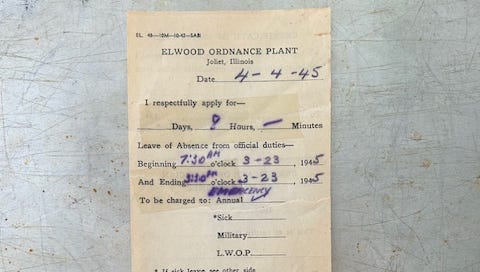

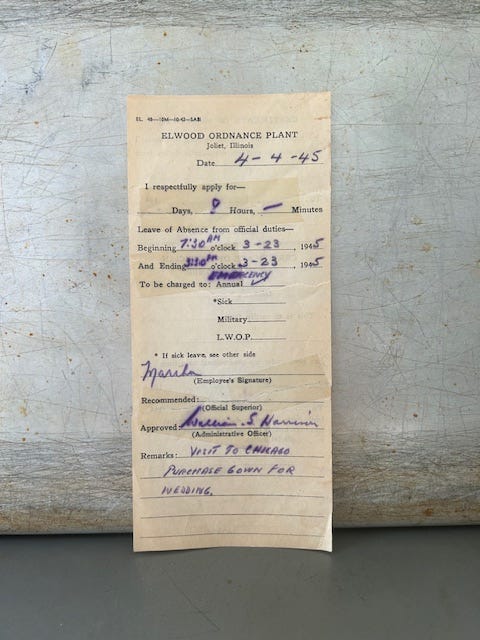

“I found this form 75 years after she filled it out: a request for eight hours to go to Chicago to buy a wedding gown.”

Thirty years after my mother’s death, it feels like she still haunts me. Until she died, when I was 28, I wanted nothing more than to get away from her, and yet all these years later I can't get her out of my mind. (Or out of my writing, it seems. She appears in almost every personal essay I’ve written, even when they were not supposed to be about her.)

I found this form in a box of her papers 75 years after she filled it out: a request submitted at the munitions plant where she worked during World War II, asking for eight hours to go to Chicago to buy a wedding gown. Why had she hung onto such a thing? And why didn’t the form’s dates jibe? And why the word EMERGENCY? My parents’ wedding wasn’t till late December. Had an unplanned pregnancy made them anxious to marry in spring? And then maybe she miscarried, as she would later be prone to do, so they put the wedding off? I had questions, but my dad also had died. There was no one alive who could answer.

What I do know: She had a very difficult relationship with her own mother, an invalid who favored my aunt. My mom quit high school her freshman year, and at some point while she was still a teenager, my grandmother kicked her out and she went to live with a cousin in a home for single women. When she returned to retrieve her belongings, my grandmother and aunt had burned them. At least that’s the story she told when she’d had too much to drink, which was often.

She also reminisced about the fun she had when she was single, the dances she attended and how all the boys liked her. My father certainly liked her. He thought she was a joy.

I think she thought getting married would save her. But my father said that after she gave birth to my brother, she “turned,” becoming mean and manipulative. I think she had postpartum depression. She also likely had an eating disorder; she was proud to say she weighed just 89 pounds after giving birth. She was physically and emotionally abusive with my brother. I think she just didn’t like having children. She also didn't like to be touched, yet she kept getting pregnant. After my brother was born, there were at least three miscarriages.

My father planned to separate from her (but still support her) after my brother graduated from high school, but when she was 40, she carried me to term. She promised my father she'd be better with me. She wasn't. We fought constantly. She hit me often. She once spewed that she wished she had aborted me. Around anyone other than family, though, she was kind and generous. The life of the party. Funny and smart and loved a good joke. People adored her and thought I made up the abuse.

I think if she had come of age at a time when women had more options and therapy was more common, she might have been different. More caring, maybe. More loving and forgiving. Happier. She might have become the person she imagined being when she filled out this form. She was just 19 then, a girl hopeful for the future, excited to start a new life. I keep the form because it makes me feel sad for that girl. I feel, for the first time in my life, sympathy for my mother. Sympathy I didn’t have even when I had my own mastectomy, 30 years after hers. Sympathy I wish I’d been able to feel while we still had time.

—Donna M. Airoldi

Donna M. Airoldi is a Brooklyn-based writer and journalist.

For a different reading experience, The Keepthings’ stories can also be read in their entirety on Instagram @TheKeepthings.

Have a story to share? Please see the complete submission guidelines, including photo guidelines, at TheKeepthings.com.

Brilliant and so heartbreaking. And yet our urgent task, if we're ever to become fully adult, is to see the flawed humans that became our parents as separate people outside of their roles as the imperfect, sometimes wonderful or even terrible caretakers they were. What a generous and engaging essay, beautifully written.

Donna, thank you for sharing your heart and soul with us. It is never easy to tell the truths of our childhoods. I know it is hard, and I understand about finding parts of your mother in all of your essays, it is that way with my own father. I applaud your bravery, and I am so glad you were able to find sympathy for her. It is difficult and complicated to heal after our parents are gone, but in the end, compassion for ourselves is what matters most.