WHO ARE YOU MISSING TODAY?

For me, it's my Nana Pauline.

For the past year, in fits and starts, I’ve been sorting through the contents of my basement. Yesterday I found a little trove of correspondence from my dad’s mom, my Nana Pauline—cards and notes she sent when I was in my thirties, living 600 and later nearly a thousand miles away. Just the sight of her handwriting overcame me with my love for her and hers for me. (Handwriting that at this point in her life pained her not just to produce but to behold, as arthritis and rheumatoid arthritis made her hands ache and her fingers stiff and her penmanship sometimes wildly crabbed; more than one note interrupted itself to exclaim/apologize, “Can you read this?”—her indignation and frustration loud and clear.)

For more than twenty years I’ve kept on my desk a framed copy of the last words she ever wrote me, when I was nine months’ pregnant: “Think of you all the time, and I am counting the days with you.” Yesterday—among notes in which she admired magazine essays I’d written (“I like your style”), sent love to my husband (though she had yet to meet him), thought back to ballet recitals and Easter-egg hunts of yore (“Remember?”) and thanked me again for the time I drove ten hours to visit (“I’ll never forget”)—I found the actual card in which those last words were written. “Think of you all the time, and I am counting the days with you.”

She didn’t make it. She died on April 10, 2002, fifteen days before my child—her first great-grandchild—was born. It's the sorrow of my life that they never met.

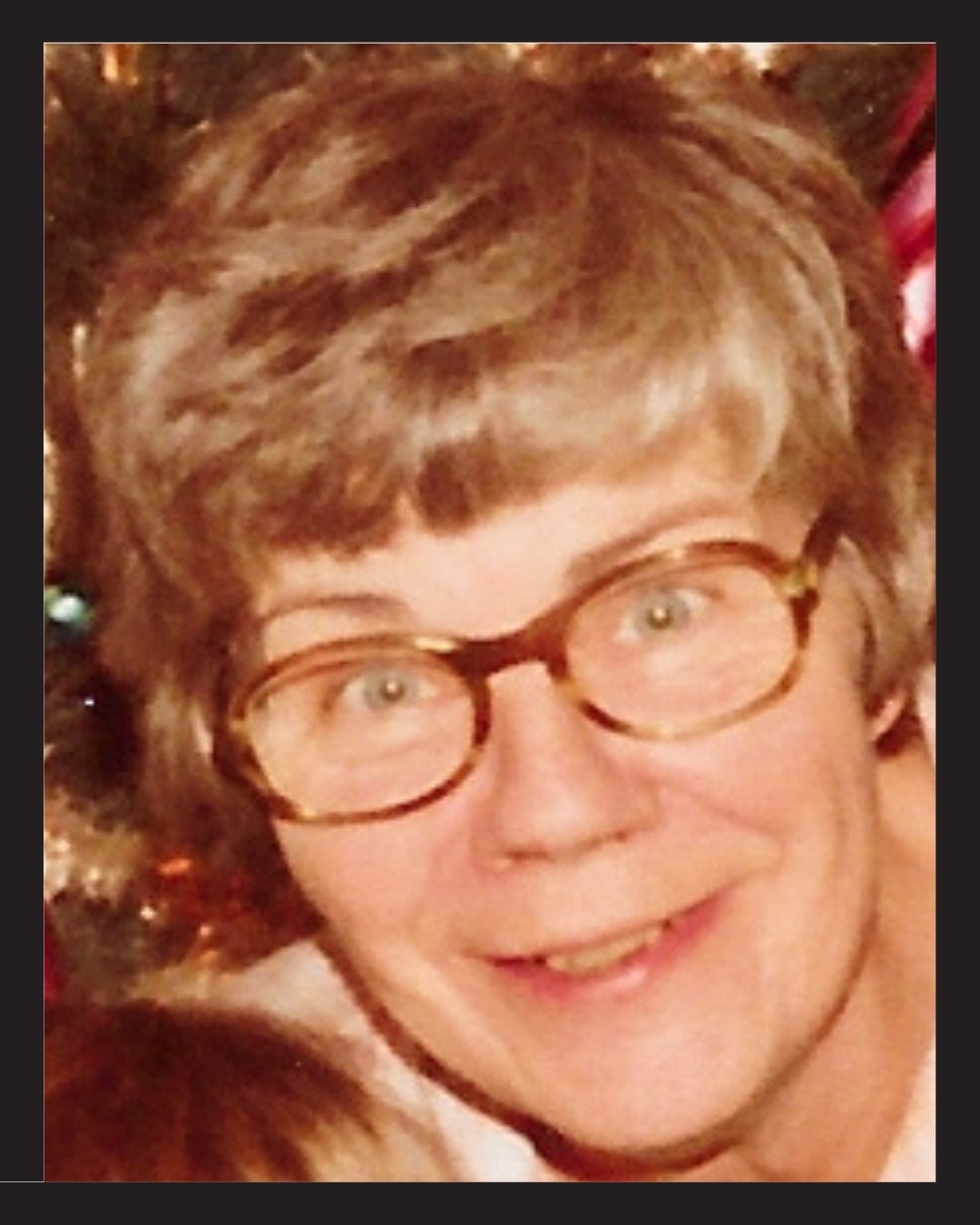

Even as a little girl, I understood that Pauline had the sharpest of tongues and the hardest of edges. Extremely competent and sensible herself (whether cleaning, baking, gardening, driving, playing cards, telling a story or talking Phillies), she suffered neither incompetence nor nonsense in others, and everything had to be her way. But she was a lunatic with love for her grandkids; in the above photo the residual crazy gleam in her eyes is because whoever took the picture—probably my grandfather—had just caught her in the act of devouring my little toddler cousin. (She always laughed that she couldn't take a good picture to save her life, but to me she looks perfect here.)

I was too pregnant to go to her funeral. Still, part of me is thankful I never had to see her in a casket. What I wanted, what I’ll forever want, is to open her front door—“Anybody home?”—and hear the joy ring out from her kitchen: “Just us chickens!”

So, now, who are you missing today?

My father died 20 years ago and his birthday is next week. Twenty years seems an impossible number. I am now closer to the age he died than to the age I was when he died—a grief math that leaves me unmoored. Just a few days ago I ached to just sit at the breakfast table and talk with him. He would talk current events with me when asked but would never force a discussion. He didn’t mind disagreements but avoided confrontation or a raised tone at every turn. He never dismissed with a “you’re too young to understand.” What would he say about today’s world? Would he have advice or admit his own lack of knowledge to make sense of such senseless cruelty and chaos. Every time I smell fresh cut wood I think of him; he was an hobby woodworker who made toys and furniture. Every time I see a cloth recliner, I am still transported to the feeling of crawling into his lap for an extended hug, even into my teens. He was around to see my two children but my youngest says: I don’t think I have any actual memories of him, but I have so many memories of you telling stories about him that it feels like I knew him. And that is the greatest comfort I’ve found.

That's an interesting photo of my mother, Pauline (Faulstick) Way, Deborah's Nana Pauline. Normally she would exhibit a sort of frown as she tried to force a smile.

Talk about memories! I could write a book about her. One memory that stands out is her taking a job to make it possible for me to go to college. She worked at Binney and Smith Co. on the 6pm-12am shift. She ran machines that labeled and packed crayons. The work involved handling thousands of crayons each shift. That contributed greatly to the arthritis that damaged her fingers.

Now, in the winter of my life, I'm so glad for all the memories. They add happiness to each day. Sadly, I have questions about things that could only be answered by Mom. I wish she were still here to provide answers. My advice to younger generations is to ask questions of your elders while you can.