THE TEXTBOOK

“...I remember what it was like to walk into the hospital with him, the great surgeon.”

Elephantiasis—a disease that made your legs wide as tree trunks and scaly like an elephant’s. Argyria—your skin turned blue from eating too much silver. Leprosy—that rotted off your fingers and toes and nose. I pored over the illustrations of these conditions. They were found in a book called Diseases of the Skin that my father kept along with other medical texts in his study at our house outside Philadelphia.

One day I asked him if I was in danger of leprosy, and he said “I doubt it” but didn’t rule it out. This worried me, but I didn’t say so. He told me he was writing a textbook himself, about the doctoring he did, which I knew about from going to the hospital with him to play quietly with his child patients who’d come from places around the world, often alone, to have their hearts fixed. I also stood on a balcony above his operating room to watch him, though surgical hats and drapery obscured my view.

He told me that in World War II he’d been an army doctor and worked in hospitals in India. Soldiers hurt on the battlefields of the Far East were flown there for serious operations. In wartime, doctors saw wounds that needed surgeries unlike any they’d ever performed in civilian life, and many new procedures were invented on the fly. He’d had time since then to routinize these surgeries, and he was writing them down so other doctors could learn them.

This, he told me, was why on most summer weekends, he didn’t come down to my grandparents’ house at the shore. Or if he did, he stayed in a hotel and met us for a few hours on the beach. When he took off his shirt to swim, I saw the J-shaped scar on his back that ran from his neck to his waist. He’d had a disease called tuberculosis that cost him a lung. The skin of the scar was thick and hard, but it didn’t look like the diseases in the book. Scarring is a process of health, he told me. A scar shows a wound is fixed.

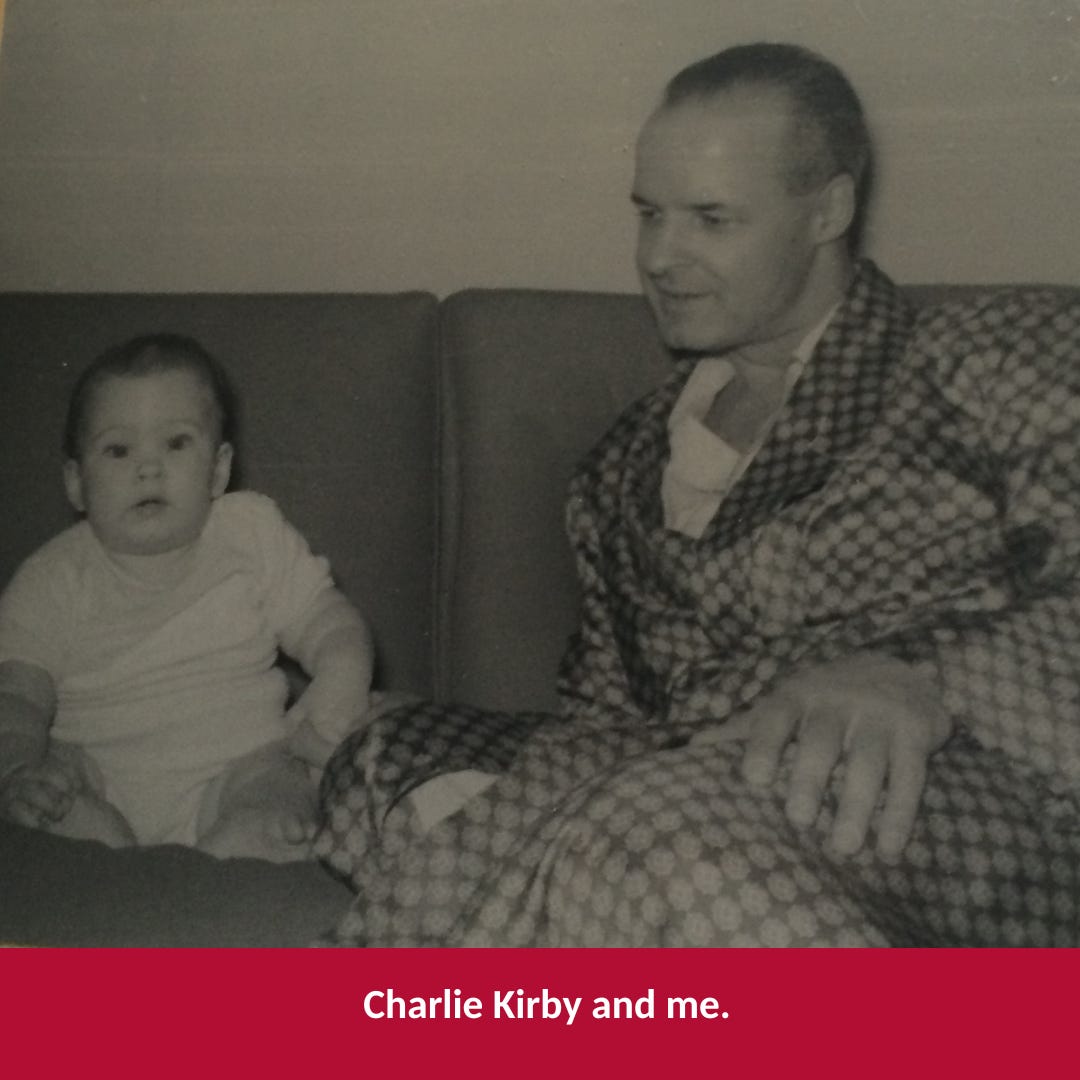

The real reason he stayed in a hotel was that my parents were headed for divorce. Then, when I was ten, my father died. These events occurred in an era when people believed that mentioning divorce or death to a child was harmful. The effect was that my father vanished, and I received no mementos of him, not even his textbook. Many years later, my husband found this copy on the internet and bought it for me.

The book’s forward doesn’t claim ownership of any techniques, instead stating, “Progress in thoracic surgery has resulted from the efforts of a great many individuals.” I appreciate the modesty, but I remember what it was like to walk into the hospital with him, the great surgeon. Doors flew open, people stepped back and hugged the walls. Did they bow their heads as he passed? It seemed so, to me. After he died I clung to his accomplishments: the first artificial mitral valve, patents for parts of an artificial heart. I clung to the few words I remember him saying, including his doubt that I’d get leprosy.

I wanted much more from him, more time, more conversations. Instead I will always be marked by his death, as his back was marked with his J-shaped scar. I have to make what I can of what I got. The textbook, for example. It isn’t just a record of his surgeries. I take it to signify that he was a writer, too.

—Alice Elliott Dark

Alice Elliott Dark is the author, most recently, of the bestselling novel Fellowship Point.