THE SUN HAT

"I can picture her walking through that posh shop picking up different things...."

In June 2000, a month or so before she died from a fast-moving cancer, my mother was invited to spend a few days at a friend’s house in the Hamptons. It was the kind of magical thinking that possessed us that summer, that a person might be cured by a few days in the sun.

I don’t know much about her trip to Bridgehampton, but I remember she came home early because she wasn’t feeling well, because she was in fact sicker than any of us knew, than she knew.

When she came home, she gave me this pink cotton sun hat she had bought at a shop in town. As I recall, she’d walked to the shop from her friend’s house and it had been a lot for her. The hat was too small for me so I have never worn it, but I have also never given it away.

When my mother died, I was 27, struggling to get by on low-paying jobs in New York City. She was struggling financially too; she had been fired a few years earlier from a job in the fashion industry and was just getting back on her feet. She didn’t have a lot of extra money to help me buy the things I thought I needed for a grown-up life: a blazer or a good pair of boots or a leather handbag. I had friends whose mothers could buy these things and sometimes I felt resentful. All of which is to say she didn’t often give me gifts, not at that time in my life.

When I had children, children she never met, I understood better why she bought me the hat. When my children were little, and even now when they are big, I am often gripped by a desire to buy them gifts when I am separated from them. In fact, when they were small enough to still need a babysitter, I would sometimes spend my few hours away from them shopping for gifts to bring home. Because I missed them and wanted to give them something when I returned.

The sun hat tells me that my mother must have missed me—even yearned for me, yearned to be close to me—during the few days she spent in Bridgehampton. I can picture her walking through that posh shop picking up different things, holding them by turns in her hand, testing their weight and value before settling on the hat. This, she would have thought. I’ll get this for Daisy. She was exhausted and unwell and couldn’t handle much more than a simple cotton hat.

My mother was only 56 when she died, in the middle of a rich and beautiful life. After it was all over, we were in a rush to clear out her apartment—again, because of finances—and in that burst of grief and cleaning, a lot of things got tossed or given away. I sometimes wish I could go back and do it all more slowly. But I’ll keep this hat, simple and unwearable, forever, not just because it is the last gift my mother ever gave me but because it connects me to her as a mother myself, even though she never knew me as one while she lived.

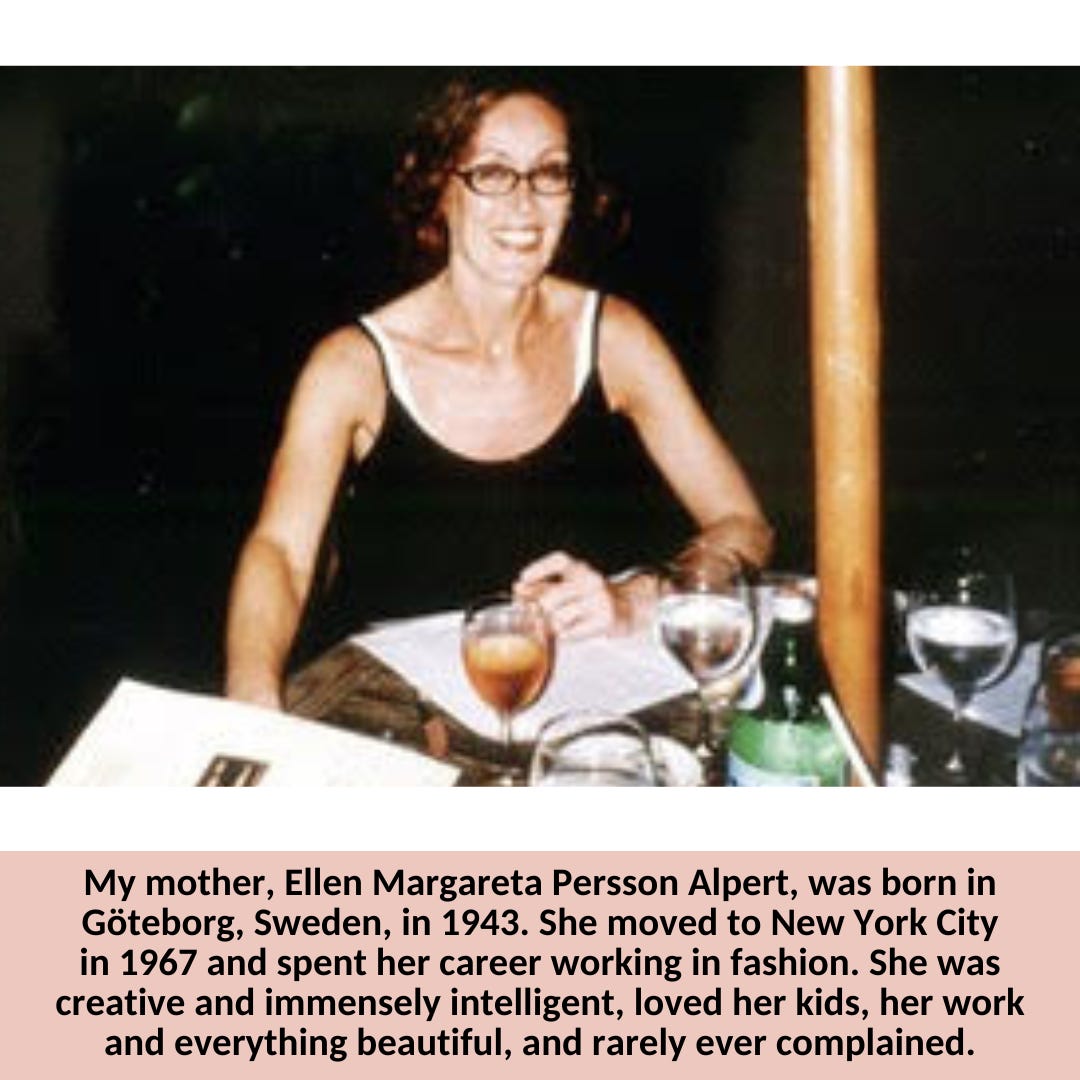

—Daisy Alpert Florin

Daisy Alpert Florin is the author of My Last Innocent Year, a New York Times Book Review Editor's Choice and USA Today Must-Read Book. A native New Yorker, she lives in Connecticut with her family and writes a weekly-ish newsletter, Girls With Feelings.