My mother had exquisite taste. Even the things she owned that I didn’t like—you could tell they were beautiful: well-designed, exceptional examples of their specific styles.

I remember trips to Lord & Taylor as a child, stopping to listen to the piano player while she tried on dresses or colorful, flowing pants that I just loved. She always looked so graceful and elegant. I still run into people who tell me, “Your mother was the most beautiful woman I ever knew.”

She was particularly drawn to anything Art Deco, and had an eye for designing her own pieces. When a friend bought a pair of earrings, my mother convinced her to turn them into rings because “they’d just be so much cooler that way.” She designed her own wedding ring (a circular diamond flanked by 2 oval-cut sapphires), and she’d wear something backwards if she thought it hung better that way. She made earrings out of fly-fishing hooks from my grandfather and received compliments every time she wore them.

As I got older, there was a divorce and money became much tighter. No more trips to Lord & Taylor, and my mom had to get a job. She started substitute teaching at Barrington High School—my high school—a nightmare I couldn’t believe was real. At this point, thankfully for 15-year-old me, she had a different last name from mine. But I remember being in clubs after school with kids I didn’t know well, listening to their stories about the crazy sub they’d that day, knowing full well it was my mom and just praying none of my friends would let on.

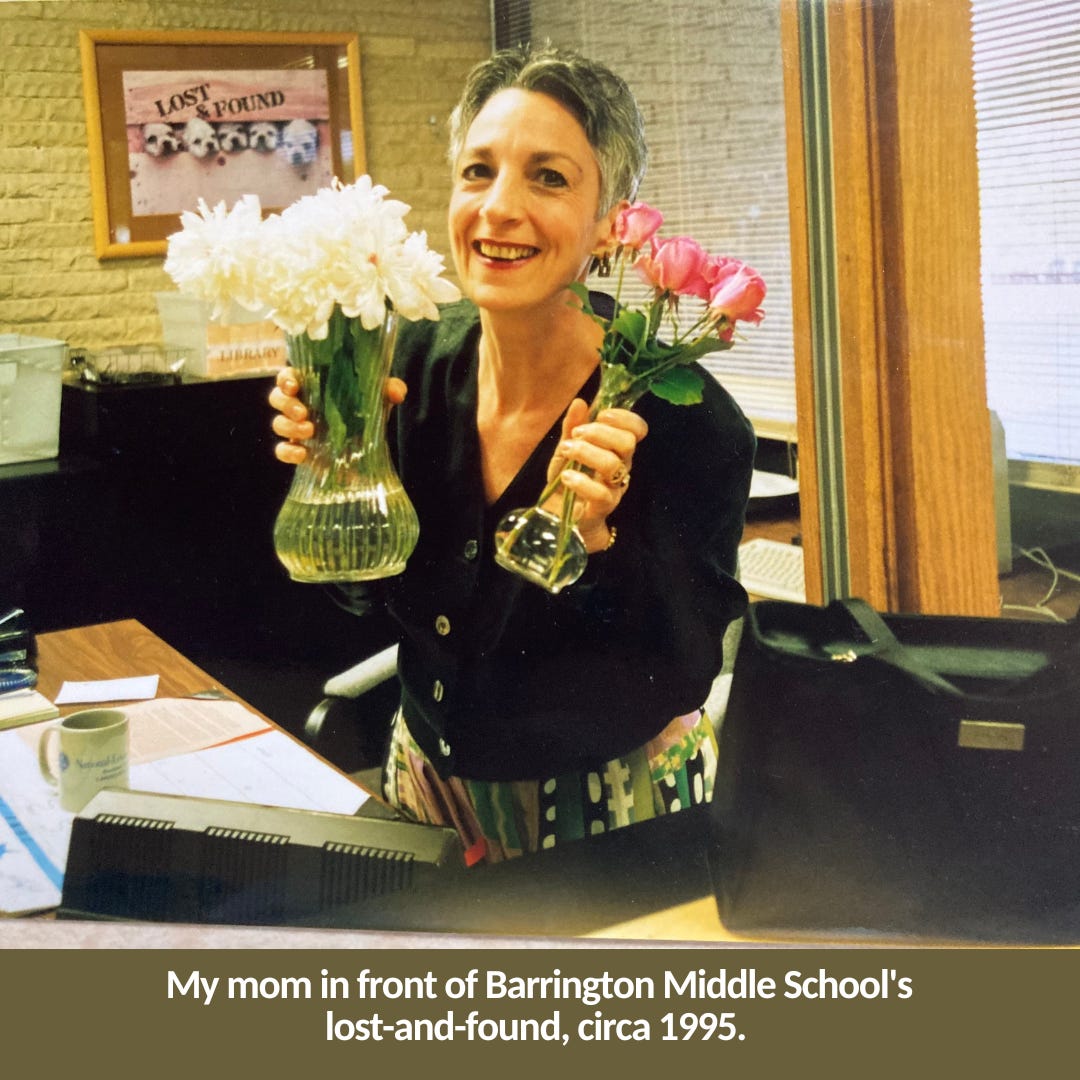

When I went off to college, she got a job as the Office Lady at the middle school in my town. And she started collecting jewelry that had been left for too long in the lost and found. Compared to the exquisite jewelry she already had—garnets from my grandmother, amethysts in silver, Art Deco pieces she’d chosen or designed—this was a bizarre assortment of trinkets. Things a 13-year-old girl would treasure for a couple of months, max.

So I’ve saved lots of jewelry from my mom—her wedding ring, some of the beautiful pieces she collected, the rings her friend converted from earrings—but also, for some reason, this small, soft-sided container of middle-school lost-and-found items that weren’t dear enough even for their original owners to miss. Without getting too philosophical or waxing too poetic, I think there’s something about the fact that she found as much beauty in them, in a different way maybe, as she did in her own exquisite collection.

It seems to be a human thing to idealize those we lose, and to remember the very best parts of them. But I like to remember the less shiny, less perfect bits because those facets make a more complete picture, which for me is the real beauty. I guess the junk jewelry is a symbol of that.

—Brooke Rogers