THE LAST BOBBLEHEAD

“High off his joy, I said, ‘Yes! Buy all these odd man-toys.’”

I’ve always been into weird, and Randy served it up hard. He was an outgoing introvert who loved pop culture and had a booming laugh that sounded like a horn. In 2007 while visiting San Francisco, we found a bobblehead emporium full of Sunday-morning cartoon characters from his childhood. High off his joy, I said, “Yes! Buy all these odd man-toys!” And made room in my suitcase so his new obsession could come home to Chicago.

The following year Randy and his bobbleheads moved in. I was excited about half that deal. Then: marriage, a new house, grad school, a director-of-digital-marketing job, his beloved White Sox winning the World Series, and eventually four babies. Along the way the bobblehead collection grew to more than 400. Randy and I argued some. We laughed more. If he said something, he meant it. If he said he’d do something, he did it. Our conversations included lines from TV shows, movies, commercials, theme songs. We had our own language. We were rock-solid, I-choose-you-always legal best friends with benefits.

In February 2019, he collapsed on our stairs. A healthy 37-year-old who never smoked or drank (seriously—growing up, he had bad asthma and migraines and was told no tobacco, alcohol, or caffeine, so he didn’t; he was a logical robot that way). Doctors said he had a virus. But symptoms persisted, and that May he was diagnosed with primary heart cancer. In June we relocated to Houston for treatment. If the doctors were right (which they were) that October was the most we could hope for, we had only a few months left for Randy to sing “Twinkle, Twinkle” to our girls, aged 2, 4, 6, and 8.

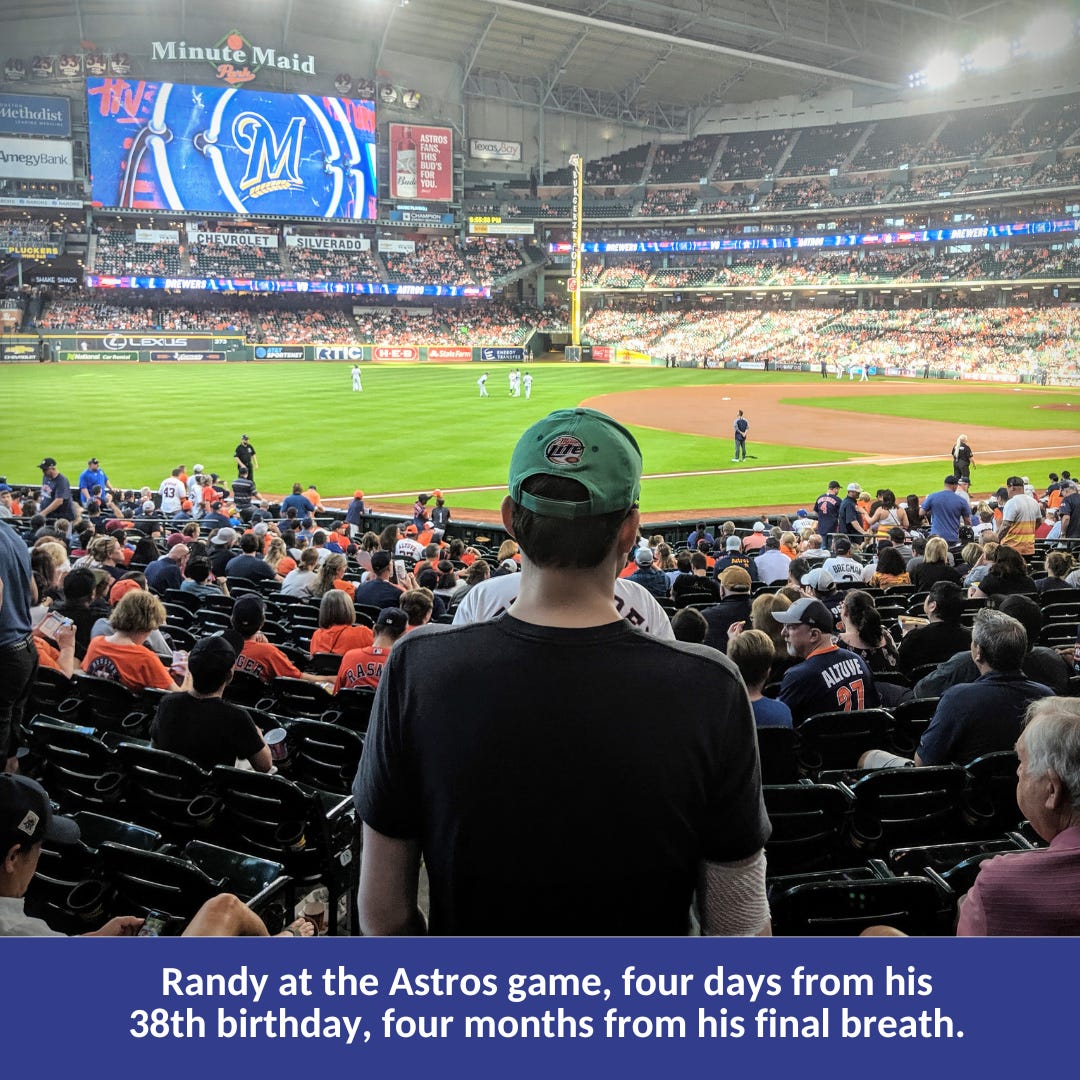

During a break from hospital stays, Randy bought tickets for the June 12, 2019, Houston Astros game. In a stroke of lucky timing, it was bobblehead night. I said, “Yes! Spend all the money, splurge on the best seats!” Responsible as always, he paid $65 each. I teased him: “Okay, wild man.” But when the day came, he said he wanted to stay home. I pushed: “Your hemoglobins are at an all-time high. I think we should try.”

The driver dropped us at the ballpark, a 15-minute ride from our beautiful borrowed blue house. Randy collected his complimentary bobblehead and I stashed it in my bag. Wary of the crowd potentially bumping his chemo port, I tried to shield his right arm with my body. People were walking too close, their happiness was too loud, their breathing too condescendingly easy. I resented every able-bodied stranger. “Don’t you see he’s dying?” I wanted to yell. “Move!” Randy, though, was amped by the atmosphere. Gripping the railing, he walked ahead of me to our seats.

While he watched the game, I watched him. His jaw muscles relaxed as the familiar rituals played out. He took baseball seriously. He loved the slow and steady rhythm of the game, and also knowing that anything could happen at any time. I was so proud of him for showing up, for letting reality dim enough to choose joy. When we left, mid-game, he asked me to walk in front so the crowd wouldn’t notice him. They noticed anyway: a thousand faces wondering why such a young man struggled to climb the stairs.

Every breath was a quiet convulsion as his lungs filled with fluid. Every day my best friend was farther from this world. But on our way home, Randy said, “I'm so glad we came.” We hadn’t watched from a hospital bed—we’d been outside, the wind on our faces. We held hands. We both walked. We both breathed. Back at the house, we even got a bit of sexy time in. There's only so much you can do when one body is filled with chemo medicine that can't touch another body, but we managed, and Randy was happy that part of him still worked. It was a proper date night. We said yes to it all. San Francisco-bobblehead-emporium-level yes.

—Stacy Klodz