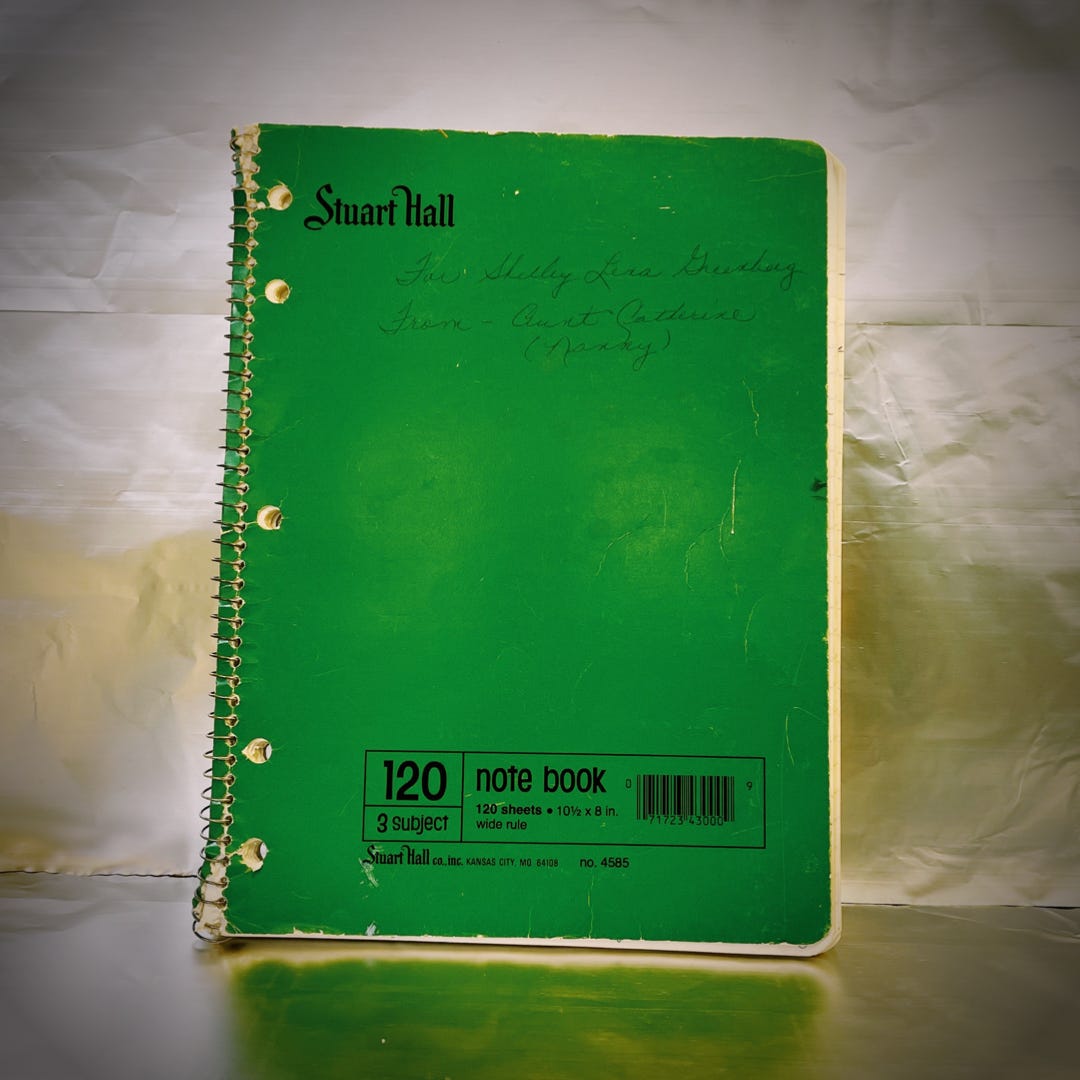

THE GREEN NOTEBOOK

“She never married or had children, and we had a special bond.”

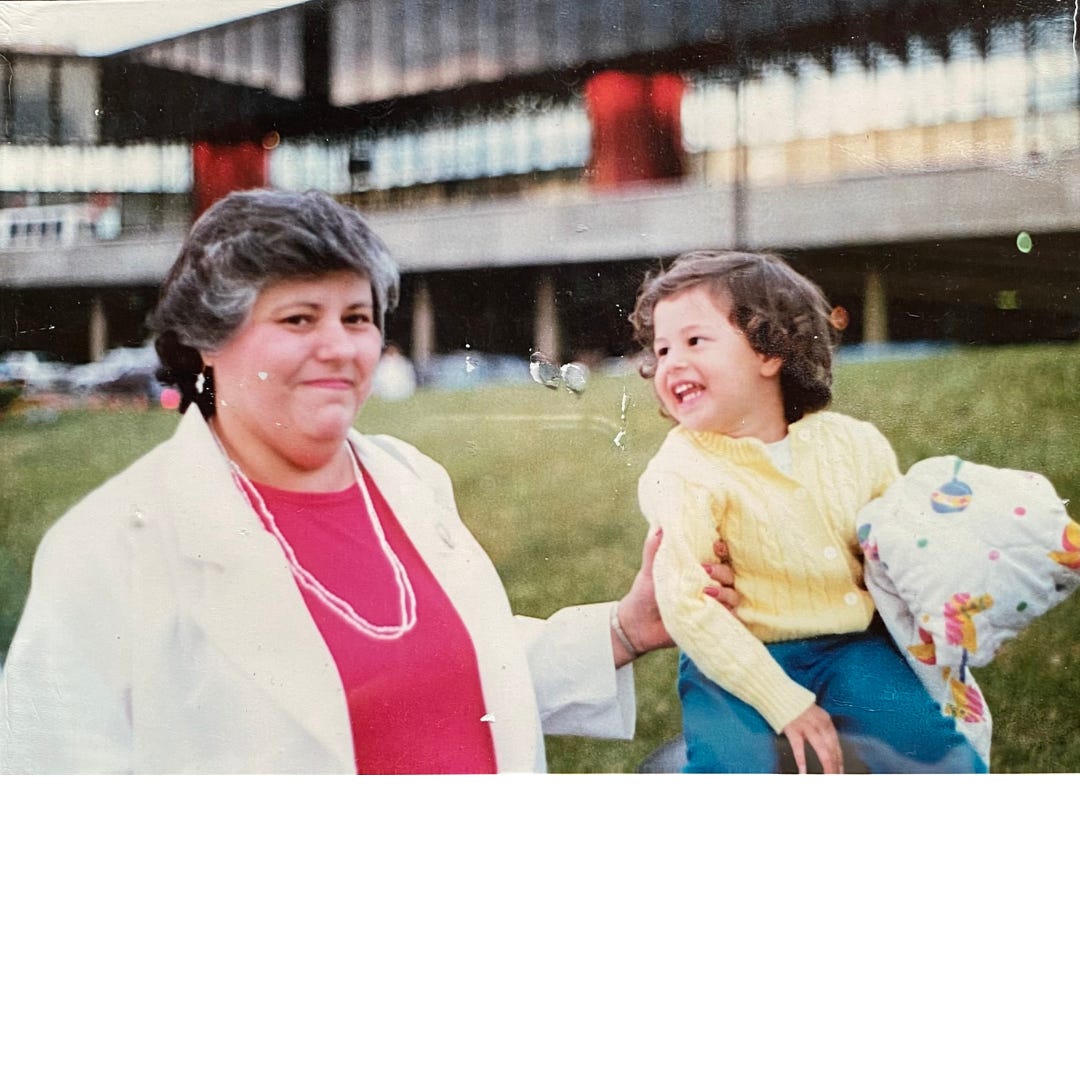

I called her Nanny, which in Louisiana is what you call your godmother. She was my mother’s oldest sibling, aka Sissy or Kitty Lou. She never married or had children, and we had a special bond. As a child, when I’d visit my grandmother’s house outside New Orleans, she was always there too as she lived nearby. She’d tuck me into bed and sing our song in her beautiful alto voice—“Baby Love,” by The Supremes.

Nanny was a lifelong smoker who was terrified of heights. She worked as a secretary, but when I visited in summer, she’d take off and have every day planned for us. In the blistering heat, she’d drive us downtown—she drove with two feet and would steer straight down the middle of bridges and overpasses if no other cars were around—and we’d ride the ferry or walk around the Quarter or go to the zoo. We loved getting breakfast at the Camellia Grill, then taking the streetcar down St. Charles Avenue. At Christmas she’d bring a cheese ball to the family party. At her apartment, she had old-timey bubble lights on her tree that I adored.

She died suddenly when I was a senior in high school. It didn’t feel real until we got to the wake and my mom leaned over the open casket and said, Shelley’s here, Sissy, Shelley’s here.

We were cleaning out her apartment and starting to divide up her things when someone—not me—found the notebook with my name on it. On the outside it was just an ordinary drugstore spiral notebook, bright green. But inside, in her practiced looping script, were pages and pages of diary entries chronicling every single time she saw me—the first baby of the family—from birth to age three. It felt like she was reaching out from beyond the veil, just to me. It was such a magical moment when that notebook was handed to me, I almost felt guilty that my other family members didn’t receive such a special thing in their grief.

The notebook entries start long and then get shorter before stopping rather abruptly. We’ve always wondered if she simply forgot about it. The last entry makes me cry:

Dec. 29, 1989

Today you and your Mother and Daddy are going home…. When we got to the airport and we had to say goodbye you kissed and hugged Mimi but you wouldn’t kiss me. Your Mother said it was because you didn’t want to say goodbye to me. Finally you let me kiss you. Believe me, I didn’t like seeing you go.

But it's the first line of the first entry that I carry with me always: Dear Shelley, I am writing this so one day you will realize how loved you are.... I now have those words—how loved you are, in her exact handwriting—tattooed across my clavicle, to remind me.

—Shel Senai

Shel Senai is a queer, non-binary writer and editor whose stories have appeared in LEON Literary Review, Citron Review and Reservoir. They've received awards, residencies and fellowships from Aspen Words, Tin House’s Winter Workshop, the St. Botolph Club Foundation and the Mass Cultural Council. They serve as assistant fiction editor at Raleigh Review.