THE GREEN EYESHADOW

"I walked from room to room...touching all the objects I associated with my mother."

I grew up in Oklahoma and went to college there, too—Oklahoma State, whose campus was about a mile from my family’s house. One day while my parents were away in Colorado so my mother could have some medical tests, I got to art history class just in time to open a letter from my father. I’d been saving it till I had a minute, knowing how Daddy could ramble on (he had a way with funny stories about life going awry, like the time his lawnmower caught on fire). But this letter came straight to the serious point. My mother’s back pain had been diagnosed as advanced, untreatable cancer. She was dying.

I was 19. I’d known that my mother’s pain was bad enough merit specialists, but I’d assumed it would turn out to be something benign. Or if not, that it could be vanquished like we thought her breast cancer was four years earlier. I folded the letter, gathered my books and stumbled to the front of the room just as the professor was beginning her lecture. I managed to say I’d gotten bad news and would have to leave. Somehow I made my way home.

The house was empty and still. I walked from room to room, opening dressers, closets cupboards, touching all the objects I associated with my mother. I stroked her kid gloves and the velvet rim of a hat she’d made in a millinery class. I flipped up the top of a powder box shaped like a treasure chest. I rummaged through bathroom drawers, fished out her Revlon Gold Frosted Green eyeshadow, opened it and inhaled.

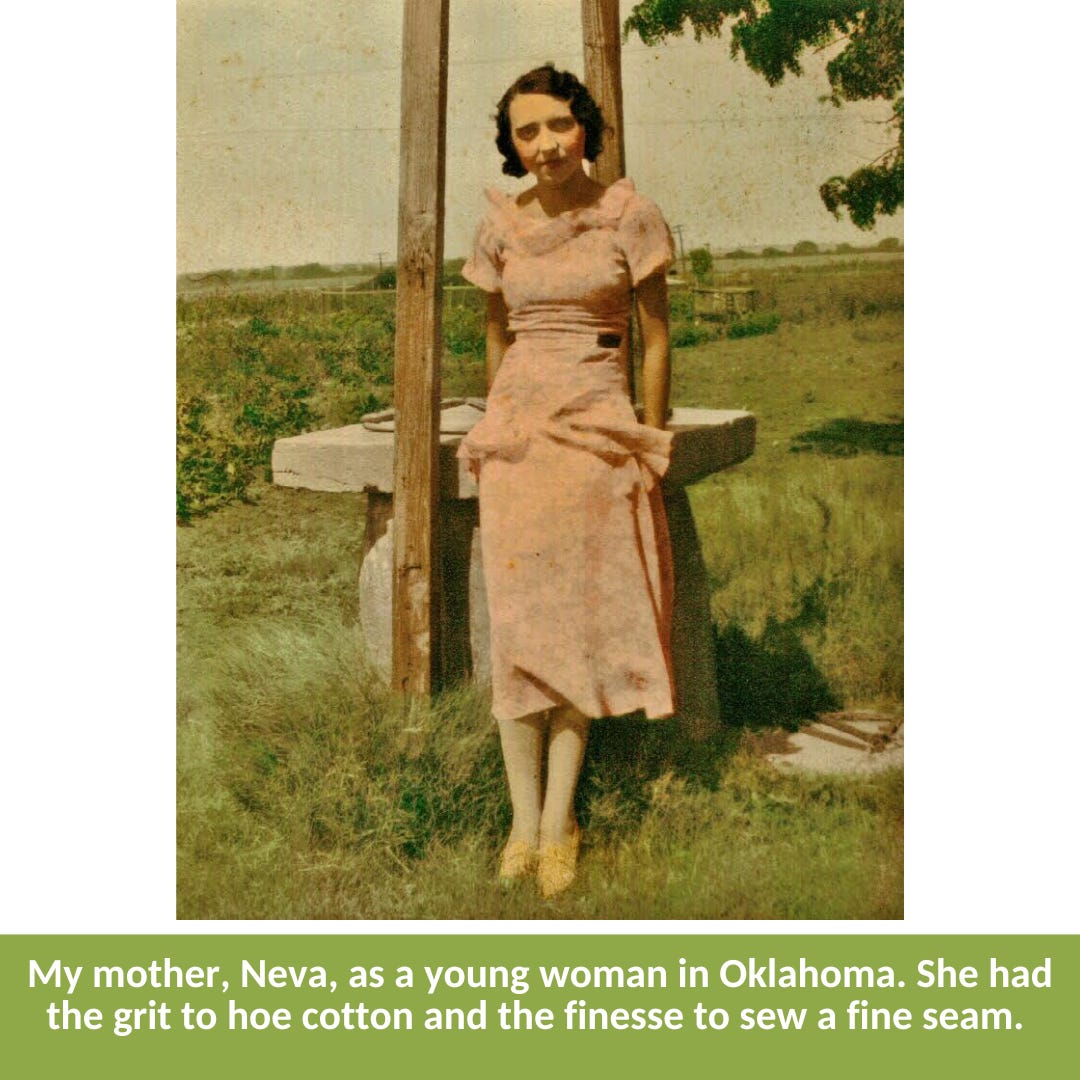

My mother had grown up in rural Oklahoma. Home alone with her little brother, she once ran off intruders with a shotgun. (I didn’t hear this from her, though—my uncle told me the story.) She married my father when she was 21, had my brother at 22 and me 15 years later. After my father finished med school, Mother never worked outside the home again. She regretted not going to college and had hoped to enroll while I was there, but meanwhile she was always learning something new. She learned to swim, play the electric organ, paint china and play bridge all in her late 40s and early 50s.

From grade school into my teens, we were very close, almost like girlfriends. We had the same sense of humor and liked to crack each other up in public, especially in situations that weren’t supposed to be funny. She was the person I wanted to hang out with after school, swapping stories over peanut butter sandwiches. We played tennis together (badly), shopped together (giddily) and, because we wore the same sizes, traded clothes and shoes.

Alone in my parents’ house that day, the scent of that green eyeshadow—waxy and slightly sweet—was the scent of my mother at her most glamorous, farthest removed from the farm girl she’d been. And it took me straight back: to childhood evenings sitting in her bathroom, watching her get ready for a cocktail party or a dance at the Elks Club. Her features weren't perfect: unruly eyebrows, crooked teeth, a nose with a hump. But when she got dressed up in a chic brocade sheath she’d made herself, when she smoothed that gold-tinged shadow onto her eyelids, where it shimmered and caught the light—to me, she was gorgeous.

It was inconceivable. In a matter of months, the eyeshadow would still be there. And she would not. All these years later, that still does seem right.

—Nan Sanders Pokerwinski

Nan Sanders Pokerwinski is a former science writer for the Detroit Free Press and the University of Michigan whose work has appeared in numerous other publications under the byline Nancy Ross-Flanigan. Her memoir, Mango Rash: Coming of Age in the Land of Frangipani and Fanta, chronicles a year of living on a tropical island as a teenager in the 1960s.