THE GRAVY FORK

“He didn’t really give gifts, at least not for typical reasons like birthdays or holidays.”

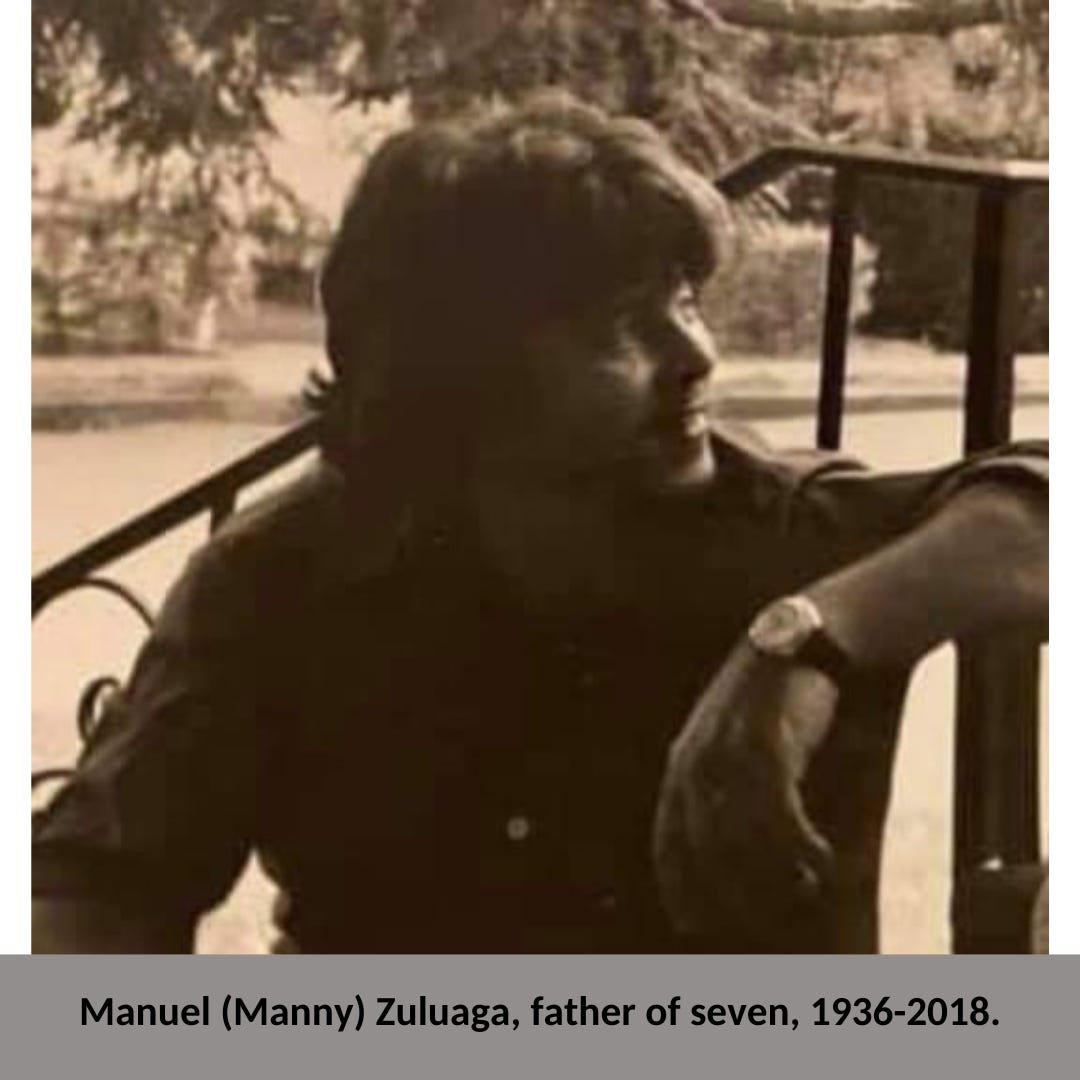

My father had a great sense of humor, he loved music and he loved food, but he was also an odd guy, uncomfortable in a lot of situations. He wouldn’t do bridges or tunnels or elevators, which meant he often took the long way, and which kept him out of hospital rooms where he might have met a brand-new grandchild. At weddings or bigger family gatherings, he’d quickly feel overwhelmed by the socializing and slip out early to sit in the car and listen to the radio.

He didn’t really give gifts, at least not for typical reasons like birthdays or holidays. There was something too awkward for him about holding something out, presenting it formally. On the rare occasion he did give a gift, it would be on a random day, and it would come from a garage sale or a thrift shop because he didn’t really patronize regular stores. Unfortunately, these offerings were almost never things anyone wanted.

All my life, I longed to tell him what I thought of his gifts: that I was allergic to the dust mites in the old National Geographics; that I wore size 9 ice skates, not size 6, and wasn’t a fan of ice skating anyway; that I didn’t need a broken camera; that my children were definitely never wearing ancient lederhosen with peeling leather straps. Instead, I took the gifts while quietly stewing over the fact that he'd known me since I was born and yet knew me so little. A cheap bar of soap with a bright smell would have made me happy, or a fat navel orange, or if it had to come from a thrift shop, a vase or jewelry box or even a tatty lace tablecloth.

My parents came to my house for what would turn out to be one of his last Thanksgivings, when he’d started to become thin. I told him ahead of time that I’d need help with the gravy. I always needed help with the gravy, since there were so many things to do at that point of the night. Also, his gravy was much better than mine. “You’ll get it someday,” he said each time he came to the rescue and took over.

On this Thanksgiving, he’d brought a container of cornstarch and a lone fork, bent so that the tines angled up and away from the handle. I didn’t pay close attention as he worked, too busy slicing bread and warming vegetables that had long since gone cold, but he put on a show anyway, straining the drippings, sprinkling in the cornstarch and using the bent fork to mix it all together over the stovetop flame.

“Where’d you get that?” I finally asked, noticing that the fork worked much better than the stupid whisk I kept meaning to throw out. “The Goodwill in Hudson,” he said. “Nice, right? You can keep it.”

I did keep it. I wanted it, probably because of its very specific purpose, like the cushioned socks you wear only when you’re going for a hike, the grain mustard you open only when whipping up a vinaigrette, the white toothbrush you brush with only when you’re traveling. And now, every time I need to make gravy, or any kind of sauce, I reach for the fork my father picked out from a thrift store and used his waning strength to bend to the perfect angle for me.

—Claudia Zuluaga

Claudia Zuluaga, a novelist living in New Jersey, is on the writing faculty at John Jay College in New York City.