THE GOOD LUCK BEAN

"It’s ironic that the memory of a person who occupied such a huge part of my life is embodied in a tiny keepsake...."

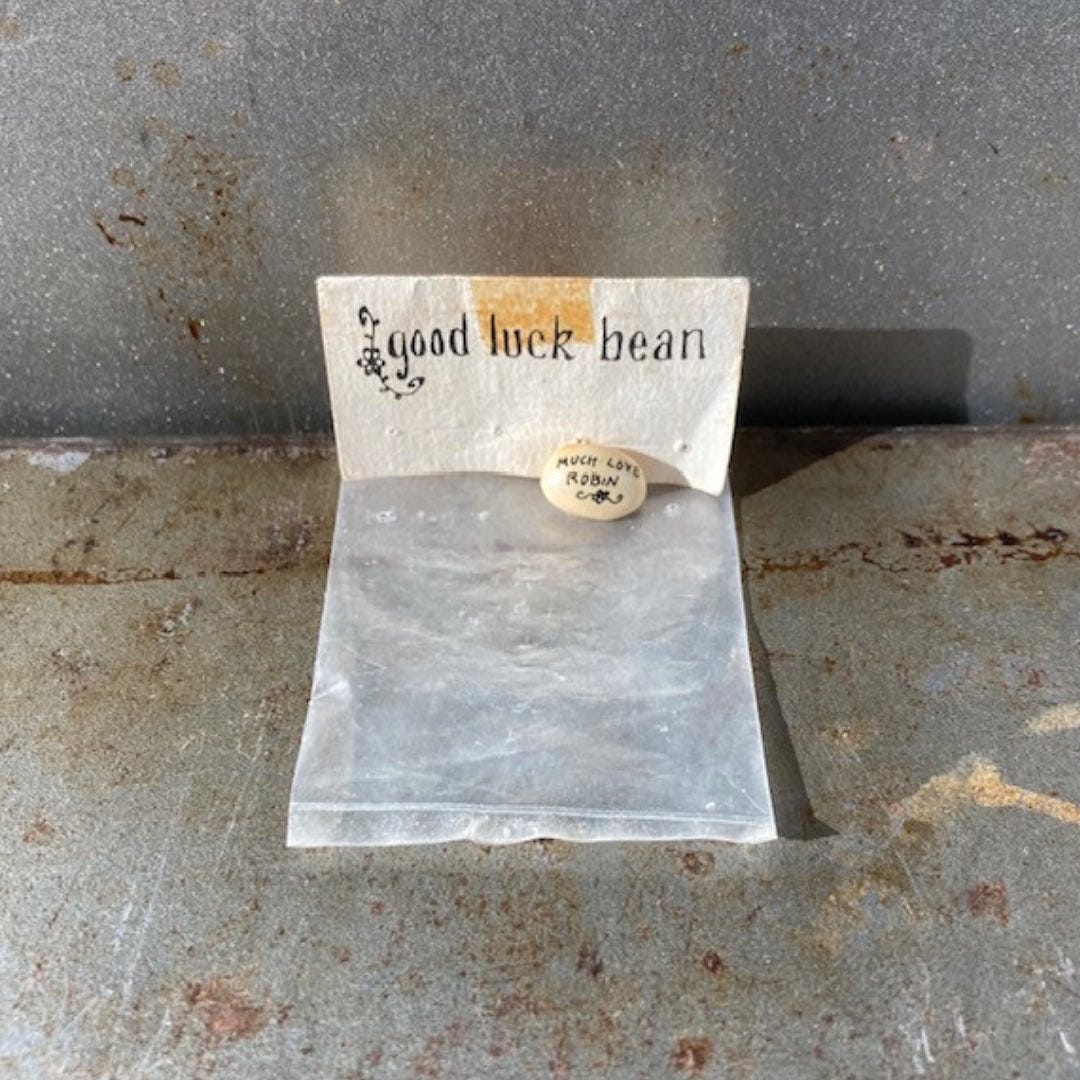

You’ll need to squint and even then you can hardly read it. The inch-wide bag has a label that says good luck bean. Inside is an actual real live navy bean, no bigger than my pinky nail. On the bean, an artist has inked HAPPY NEW YEAR OLD BEAN. On the back it reads MUCH LOVE ROBIN, with a little scroll for a flourish. It’s ironic that the memory of a person who occupied such a huge part of my life is embodied in a tiny keepsake she gave me when we were teenagers, nearly 50 years ago.

Robin inexplicably picked me to befriend when we were in seventh grade. My parents’ marriage had ended a few years earlier and my mom had abruptly moved us from Detroit to a suburb of New York City, where she’d grown up and still had family. Until then I’d led an insular and predictable life—same kids in my class every year, whole family at the dinner table every night. Then suddenly everything familiar was gone. I couldn’t make sense of this new world where smart-mouthed boys snapped bra straps and mean girls bullied kids who were awkward and skinny and shy, like me.

Robin was the balm of those miserable years. She had a giant smile, huge brown eyes, and was incredibly gregarious. She wore white lipstick, dressed her curvy hips in bell bottoms, and showed me how to add hippie style to my own outfits. (She got her flair for the dramatic from her mom, who wore full cat-eye makeup and mink to the grocery store.) Together we banged on cheap guitars our mothers bought us and painted our bicycles hot pink and green. She taught me the words to Barbra Streisand’s “People.” I played guitar and she sang “The Impossible Dream” in the school talent show. So what if the pretty girls and cute boys ignored us? We had each other.

Except then we were moving again, this time to Miami. My mother was ill and had to ship us kids off to live with our father. I was despondent at the thought of not having my best friend anymore, but Robin had a plan: She panhandled enough quarters in the high-school cafeteria to buy me a plane ticket so I could come back and visit. And then browbeat her parents into letting her visit me as well.

Then, as people do, we lost touch. For decades. But about ten years ago she tracked me down just as my life was blowing up—divorce, layoff, foreclosure. We instantly took up where we’d left off. She’d married and had three beautiful kids, built a home on Long Island and filled it with friends, animals, craft projects, and family chaos. Once again, she got me plane tickets to visit, which I happily did several times before breast cancer took her life at 59.

But this isn’t a story about Robin’s death. It’s about her big personality and her knack for small gestures, her thoughtfulness, her humor, the way she made herself unforgettable without even trying.

The little good luck bean has survived more relocations and stints in storage than I can count, and this month it will be moving again, for the third time in seven years. When it turned up in the mayhem of packing recently, I stopped to remember Robin and everything she meant to me. She absolutely set the bar for what I expect of, demand from, and deliver in friendships. Not everyone gets to have the friend of a lifetime over the course of a lifetime, and having had Robin makes me the luckiest old bean of all.

Amy Rogers is a journalist who writes most often about topics at the intersection of food and culture. For more than a decade, she was a contributing writer for NPR station WFAE in Charlotte, NC.