THE CLOTHES BRUSH

”I’ve kept this brush on display for years, a whisper of the life I once had.“

My father, a charismatic Irishman with the gift of gab, so loved being a Fuller Brush man, he often said he’d have done the job for free. The chance to captivate all those housewives, the carousing company dinners—it was his heaven. He was funny and engaging and had a bit for any situation. When my friends were over and we walked past as he watched Gunsmoke, he’d call, “Hey Mabel! Hey Matilda!”—names so hilariously dowdy they never failed to make us laugh. He’d launch into a comical rendition of “Casey would waltz with a strawberry blonde and the band played on”—Casey being my name, me being a girl—and we’d dissolve again.

Charming though he was, responsibility was not his strong suit. He had heart problems serious enough to land him in the hospital, yet he paid no mind to healthy living. When the hospital bills arrived, he’d probably already spent the money and likely had no plan for how the bills would be paid. He drove a snappy vintage Jaguar, fire-engine red, but none of his friends would ride with him after the time he made a sudden U-turn on a busy highway at top speed.

I, on the other hand, loved riding shotgun with my dad. I was so proud the day he drove me to the S & H Green Stamps redemption center to get the Shirley Temple doll I’d begged for. How I wished my friends could see: just the two of us, on a mission. Far more often he was leaving without me, off to a meeting or to look at cars with my big brother. Riding my bike in the neighborhood, I’d spot him backing out of our driveway and be overcome by panic. If only I could make it home quickly enough, maybe he’d take me with him. Without fail, I was still furiously pedaling, heart pounding, as he rounded the corner and was gone.

After he turned 50, Dad took to announcing, “I’m not going to live forever, and before I die, I’m going to have a color TV!” On Easter eve the year I was 11, he came home with the sleek new Zenith of his dreams. I was as excited as he was, and the next morning, after I found my Easter basket, I settled in to watch cartoons. Passing me on his way to the bathroom, he said, “How’s the picture?” Moments later he had a heart attack and died.

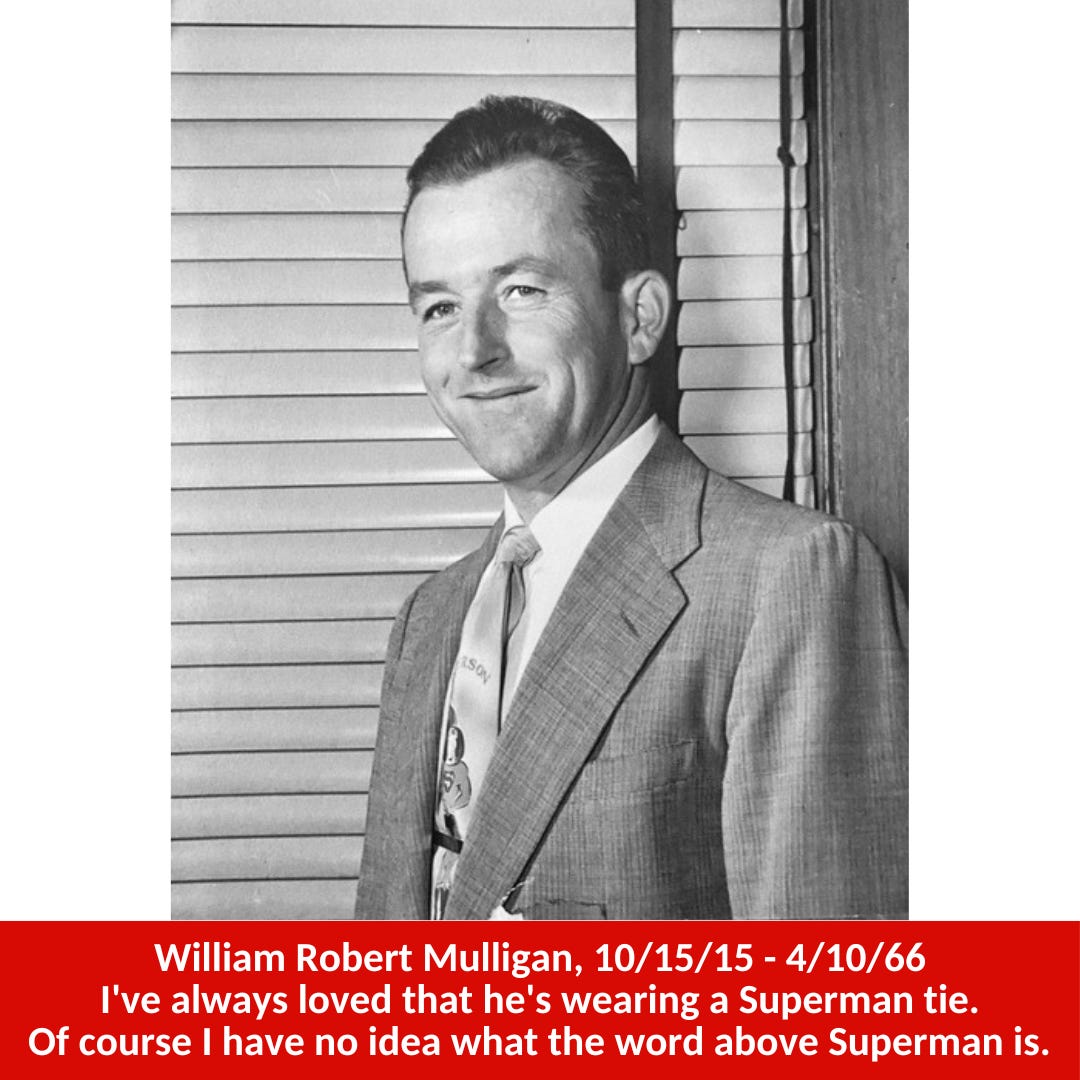

Everyone had expected my mom, who’d been battling cancer, to be the one to die. That would happen within the year. Afterward, my brother, who was 19, found a place of his own, and I was sent to relatives hours away, along with a few boxes of family treasures. Decades on, sorting through the photographs and gold-etched cocktail tumblers, I found this leather-handled clothes brush. Embossed with my dad’s name—Bob Mulligan—it sent me right back to those mornings when my dashing father, immaculate in his overcoat and fedora, went off to conquer the world one New Jersey housewife at a time.

Today, Dad seems like a character in a movie I saw long ago. The little I know about him is eclipsed by all that I don’t. I know he dropped out of high school in his senior year to join the Army Air Corps, but did he ever regret that? I know he met my mother in Baton Rouge and swept her off her feet, but were there other girlfriends before her? I don’t know his favorite movie, or color, or food. I don’t know if he believed in the God of his Catholic childhood. Did he play sports as a boy? What were his fears, and—aside from the Zenith—his dreams? I know he bragged about his beautiful newborn daughter, but did he have dreams for me?

I’ve kept this brush on display for years, a whisper of the life I once had. I always assumed it was some kind of company award. Yet recently I discovered that it wasn’t made by Fuller Brush after all. Which leaves me to wonder: Who gave it to my dad? What was the occasion? What did it mean to him? How fitting that the item that brings him back to me is as mysterious as the man himself.

—Casey Mulligan Walsh

Casey Mulligan Walsh has published in The New York Times and on HuffPost, Modern Loss and elsewhere. Her essay “Still,” about her son’s death, published in Split Lip, was nominated for Best of the Net. She’s completed a memoir, “The Full Catastrophe,” about the fight to save a struggling child and find meaning after loss.