THE BUGLER TIN

“Aloe and jade, Christmas cactus, bromeliads, caladiums and ferns filled weathered pots, leftover cans, Miracle Whip jars and especially Bugler tobacco tins.”

My grandparents lived in a single-wide trailer on Debutante Road. (The disparity between those two things was lost on me until I was older.) Because the Jacksonville heat could make being inside their small aluminum-sided home unbearable, Granddaddy built a screened-in porch that ran the trailer’s full length. This was where you could nearly always find the two of them, propped up on chaise lounges, smoking, reading, watching cars and bikes go by.

Inside the trailer, it was musty and dismal. But the porch was vibrant with filtered sunlight, and plants everywhere: Aloe and jade, Christmas cactus, bromeliads, caladiums and ferns filled weathered pots, leftover cans, Miracle Whip jars and especially Bugler tobacco tins. When the plants began to take over the porch, Granddaddy built Grandma a hothouse out of scrap wood and thick plastic sheeting. Inside were more cans, more jars, and many more pleasing aqua and navy blue Bugler tins filled with plants that had been given to her and cuttings she was starting for others.

People brought her their dying plants because they’d heard she could bring them back to life. And she could. I thought she was part witch, in the best way. I loved following her into the hothouse, a steamy cave that surged with life. She named the lizards that skittered about and would make conversation with them. A radio played country music almost continually because she believed it helped the plants, but sometimes she changed it to easy listening so they wouldn’t get tired of hearing the same old songs.

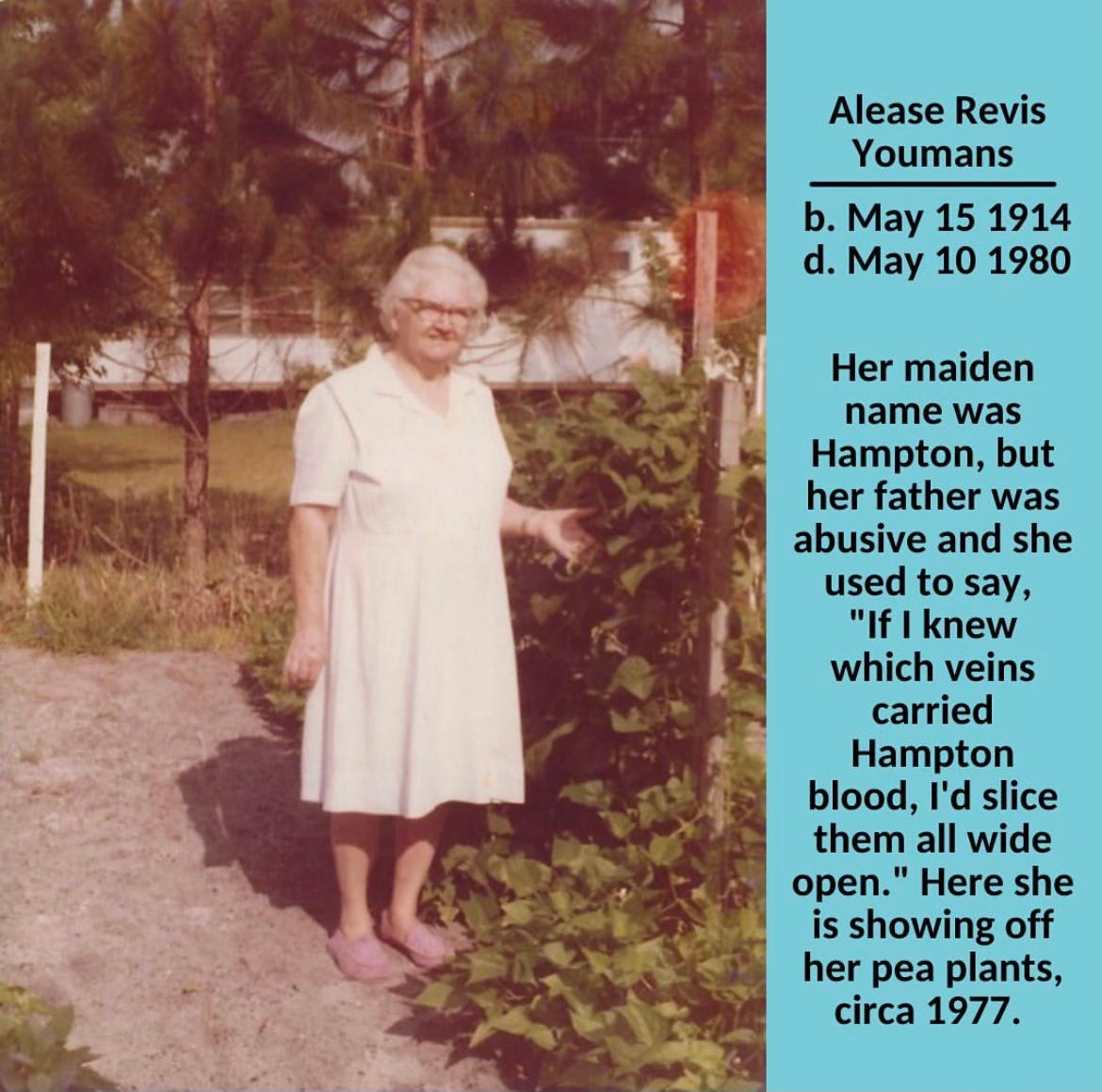

Outside, in her small vegetable garden, she’d occasionally scoop up a little bit of dirt and eat it, telling me it made her strong. If she was in a funny mood and if I didn’t ask too often, she’d move her jaw and lips a certain way that made her teeth slip in and out of her mouth! I didn’t know about dentures then.

Sunday afternoons after church, my family would go over there and hang out on the porch. I’d ask my grandparents if they needed any cigarettes rolled and was always glad when they did. Grandma could roll them one-handed, but I liked using the small orange cigarette roller—tucking the paper into the base of the machine, spreading the right amount of Bugler tobacco inside, then moving the lever up and over the hump. Out the other end would come a perfectly rolled cigarette. Well, not always perfect. She would examine them and if they were too thin, too fat, too oddly shaped, she’d tell me to give it another whirl.

Later my sisters and I would practice cartwheels, roundoffs and handsprings in the yard while the grown-ups sat on the porch talking. Grandma would call out instructions: “Get a better run at it, then push off hard from the ground!” “Keep your legs straight!” “Watch out for the chinaberry tree!” She taught us acrobatics without ever leaving her chair. She’d tell us what we did right and what we did wrong and we’d try again, over and over as it got darker and darker until darkness covered everything and all I could see of her was the glow and fade of her cigarette as she breathed in and breathed out.

—Teri Youmans

Teri Youmans is a fourth-generation Floridian who’s published two books of poetry, Dirt Eaters and Becoming Lyla Dore. She’s at work on a memoir.