THE BROWNIE SASH

“Like many children, Lydia was in a hurry to grow up.”

My daughter, Lydia, was a happy child with many interests. She was outgoing and made friends easily. She loved to wear her Brownie uniform and was proud of the badges she earned. Some of them she sewed on herself with big stitches and precise alignment. She was a perfectionist at that age.

When she asked to go with a friend to Brownie camp—a sleepaway camp—for three nights, I said no. I thought they were too young. But Lydia begged, the friend cajoled, and in the end I gave in. Then the other girl decided she didn’t want to go after all. Lydia didn’t change her mind, though. The first night there was a thunderstorm. It was all I could do to keep from waking my son and driving two hours to rescue my daughter.

On the day she was to return, I waited at Baltimore’s Girl Scout headquarters for the bus. It was hours late and by the time it finally arrived I was frantic. The girls piled off, looking tired but happy, and at last there was Lydia. In tears. I knew it! I knew it was a bad idea to send her. She was too young to be away from home. I hugged her. “What’s wrong, Baby?” I asked, expecting her to cling to me and say, “I missed you, Mom.”

“I miss my counselors,” she sobbed.

We laughed about that exchange many times in the years that followed—years in which she lost interest in uniforms and switched to 4-H, where boys knitted and girls made things out of wood, and even city kids like Lydia drove tractors. She won trophies and blue ribbons for her pet rabbits, first place for her illustrated Book of Hours. But eventually 4-H lost its allure too, as other interests beckoned. Like many children, Lydia was in a hurry to grow up.

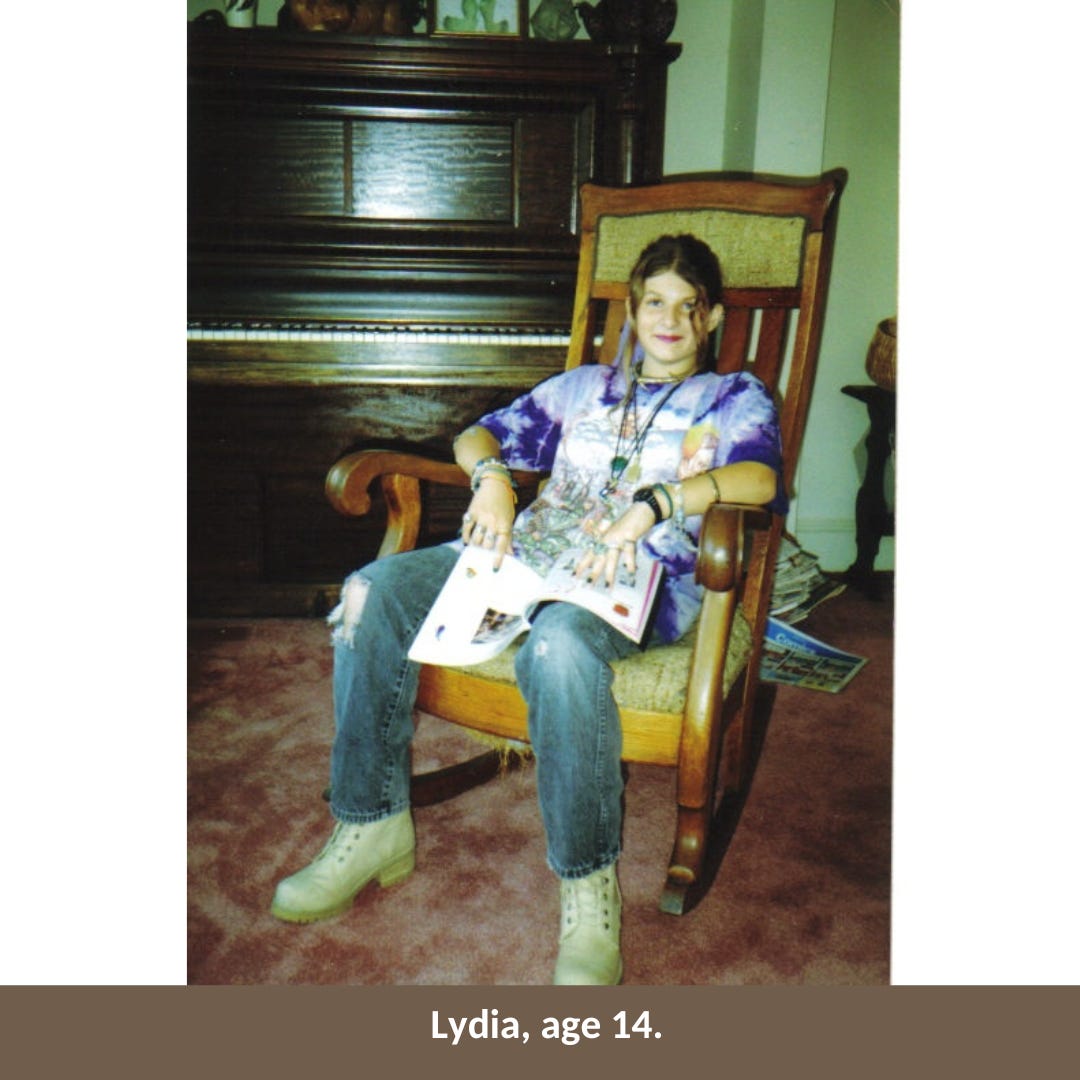

One day she gathered the trophies and ribbons and took them to the basement to make room for mannequin parts and found objects that she painted and transformed into art. Later, her ceramic cherubs went to the basement too, to make room for her books and CDs. Marilyn Manson. They Might Be Giants. Gregorian chants. Beethoven. The Cure. The precision with which she’d sewn the badges onto her Brownie sash was gone, as she grappled with depression and her room became a cyclone of clothes and shoes, journals and canvases and paints and charcoals, incense and candles, black nail polish and Manic Panic hair dye.

At fifteen, thinking she could not go on, that her time here was finished, when the antidepressants weren’t working, Lydia ended her life in that room filled with all the things she’d collected but that could not give her happiness.

And in a different house, far away, I long for the chance to let the music blare as loud as she wants. To buy her favorite nag champa incense. To see the art she had yet to make, read the stories she had yet to write. To admire the piercings and tattoos she said she would get as soon as she was old enough. To spend another sweltering day at the county fair among the rabbits and livestock. To sew a badge onto a Brownie sash. To hug my daughter and say, “I miss you, Lydia.”