THE BROKEN NECKLACE

“She cared much more about eating Pirate’s Tings with me, talking and laughing into the wee hours, than about any crap jewelry I gave her….”

I made my friend a necklace, only I made it badly—I used the wrong kind of wire—and it broke, and she gave it back to me to fix. And then she died. And I never fixed her fucking necklace.

It doesn’t matter. She didn’t care. As my father would say, it is a total nisht geferlach. And as she would say, “Oh, please.” She cared much more about eating Pirate’s Tings with me, talking and laughing into the wee hours, than about any crap jewelry I gave her, fixed or not. Plus I have plenty of whole and wonderful things of hers. Things I took from her before and after she left me. Things she gave me, too. Cookbooks, mix tapes, striped T-shirts, her Ugg boots, a scrapbook she made to document our forty-something years of friendship, which includes the 1977 letter to her at sleepaway camp in which I predict Star Wars will be no big deal.

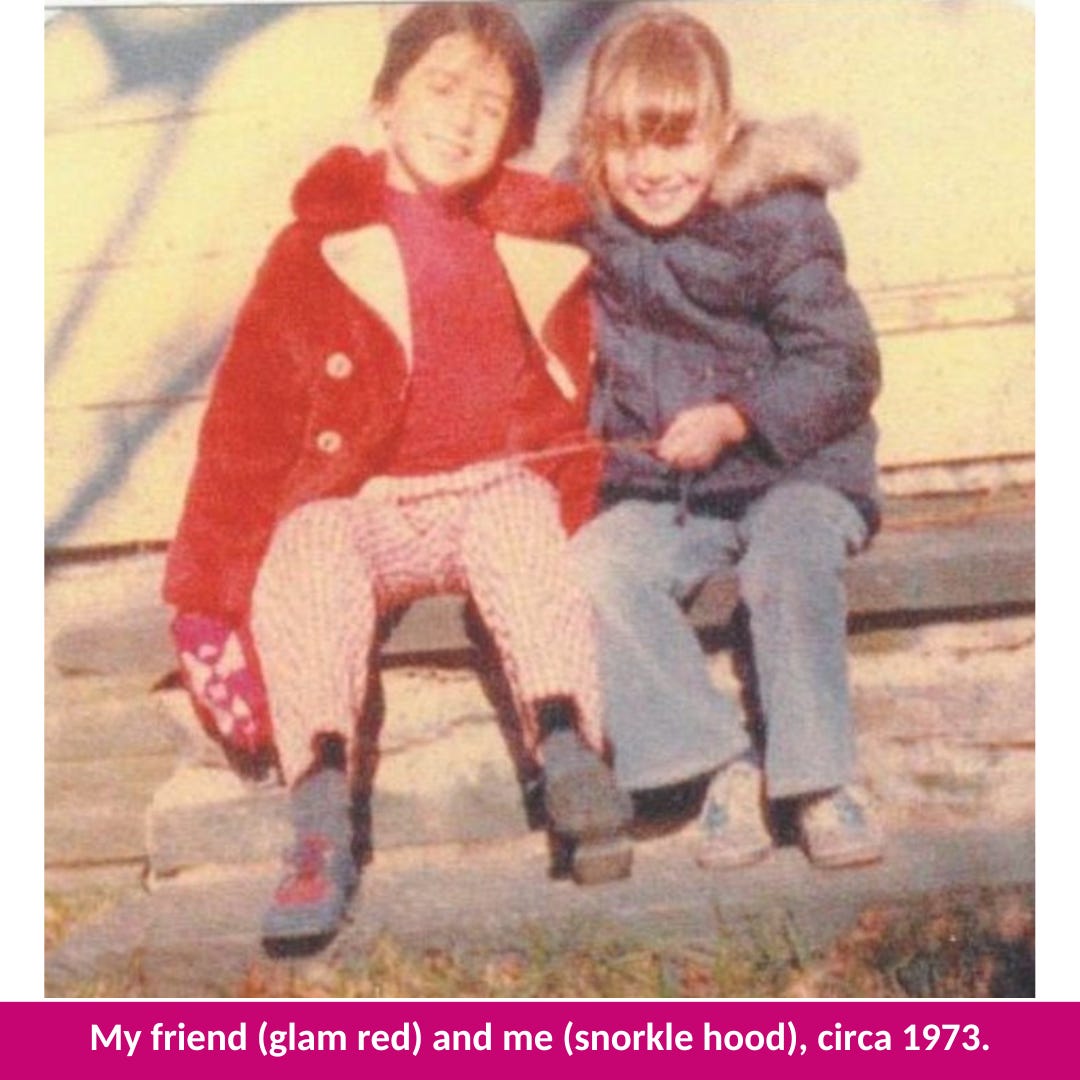

I have an arty black-and-white photograph of us posed in front of my mother’s schefflera, our middle-parted hair held back by enameled barrettes, one of us sleek and gorgeous, the other a rangy girl still missing teeth, gazing up at her. I also have three inches of wool scarf, still on the needles, which she spent hours knitting for the sole purpose of making me laugh. (It did.) There is not a surface in my house untouched by her.

This necklace, though. I put it in a box of craft materials I was giving away and then yoinked it out in a panic. It’s unwearable, but I can’t fix it now. And I can’t take it apart.

It’s not really a metaphor. She was dying for so long. We lay in her little hospice bed and whispered like girls. We loved each other so well. We had time to say everything that needed saying. Although I did inherit a 1970s-era journal of hers that said I acted like a brat at my own ninth birthday party! Which tracks, to be honest. What else didn’t I know? Don’t even tell me.

Her husband has their kids, the kids have her genes, and I have all of them—thank god—and her siblings too and all this stuff. But it’s not enough. I want to open the mailbox and find a letter that she wrote me before she died—a letter she gave someone to send me when I would need it most. Her kids are growing up, mine are grown. I take pictures of us all at the beach in Maine and think to text them to her, the way you do. “I can’t believe she’s missing this,” I say a lot when I’m with her family. But what I mean, also, is “I can’t believe I’m missing her.” I can’t believe I’m missing her still. It is so persistent, grief.

These days I'm usually brimming with gratitude for my many decades with her, for her people, for all the birthday-party advice we shared over the years. (I just found an email chain with the subject line “Piñata woes.”) I could have written more cheerfully about the photo of me sewing her into her wedding dress, or the still-intact ankle bracelet I made her when we were teenagers. I could have said true things about how lucky we were. How lucky I am still. But also? The necklace just sits here in this shitty little lidless Tupperware. Glass beads, bad wire. It is beautiful and broken forever. It can’t be made whole. So, yeah, it is kind of a metaphor.

—Catherine Newman

Catherine Newman is the author of the novel We All Want Impossible Things (an Amazon Editor's Pick, one of The Washington Post’s 50 Notable Books of 2022, and an Indie Next pick), as well as the memoirs Catastrophic Happiness and Waiting for Birdy, the middle-grade novel One Mixed-Up Night, the kids’ craft book Stitch Camp (co-authored with Nicole Blum), and the bestselling how-to books for kids How to Be a Person and What Can I Say?

That’s a lovely story. Thank you. I know this may seem odd but are you in any way related to the Newman’s from Canada? My cousin’s (Catherine) mother Nancy is a Newman from Thomas H O’Dell Newman who had sister’s and many cousins. I ask because although I’m not a Newman by name, I look (with no real intensity or fervor other than the curiosity of a cat following a ball of string) for where my family has grown and how I dangle on the end. If not, thank you for a wonderful story.