THE BEACH ROCK

“Dad found it in a tidal pool, worn smooth from being battered in the ocean’s churn.”

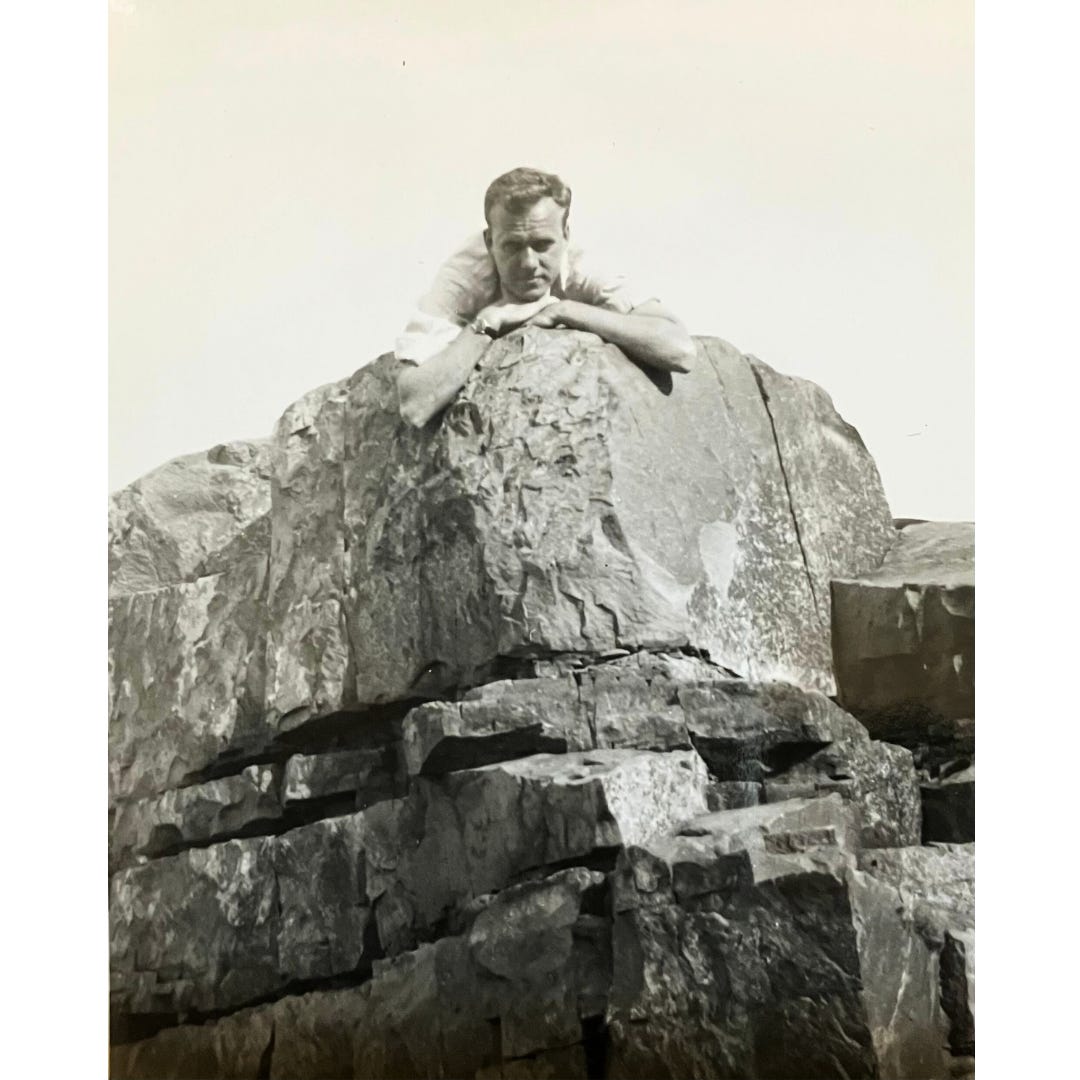

It was snowing when I took my father to the hospital the final time, and I had to drive slowly. As we crept along, Dad, huddled in the passenger seat, his normally bulky form shrunken, told me he was glad for the chance to talk. “I’ve had a good life, you know, Jenny,” he said. “A close marriage. A house perched at the edge of the sea. A lucky life.” This rock, which I keep on my bookshelf, reminds me of those words. Dad found it in a tidal pool near the granite ledges behind the home he shared with my mom. It’s worn smooth from being battered in the ocean’s churn. It’s the size of a softball, but there’s nothing soft about it.

Though he prized openness in his relationships and loved to express his thoughts and feelings—often over a vodka martini and a plate of sharp cheddar and crackers—Dad never said much about his early years. The few details he did share suggest why. When he was 15, his father died of a heart attack. The night it happened, Dad woke to loud voices and people running up and down the stairs. So unfamiliar were the sounds, he thought his parents might be having a party, but when he went to check and saw his father lying straight and still on his parents’ bed, he realized the voices had been the doctor and his uncle trying to calm his mother.

His mother became a recluse, and she tried to turn my dad into a recluse, too. She told him his friends spent time with him only because relatives paid them to. She intercepted his college acceptance letters and secretly wrote to admissions deans to say her son was needed at home. But in 1943 he was drafted into the army. War became his escape.

The beach rock doesn’t show its scars, and neither did my father. He became a professor of political science, popular with his students for his passion and wit. He and my mom loved hosting dinner parties where they served his famous chicken log and pitchers of whiskey sours. But beneath his smooth exterior, he seems to have been acquainted with despair. He wrote about the “bureaucratization of homicide”: techniques governments use to turn killing into a mundane exercise. He believed a nuclear holocaust was coming. And in the journal I found in his dresser drawer after he died, he wrote that his life had been a “fake.”

My father and I used to swim in the rough water off his beloved granite ledges. Buoyed by the swells, we stayed in as long as we could stand the cold. Getting out was tricky. The waves would suck us back to deep water if we didn’t scramble out fast. We grabbed strands of seaweed to hoist ourselves up, then lay on slabs of granite to feel the warmth of the sun.

Dad used the beach rock as a bookend for his hardcovers: Ernest Becker’s The Denial of Death, Tim O’Brien’s The Things They Carried. Books about facing darkness and emerging. I use it to prop up my paperbacks: Mary Oliver’s American Primitive, Margaret Renkl’s Late Migrations. Books about finding beauty in this world. The rock makes me think my father was wrong to give luck the credit for making his life a good one. In my view, withstanding and then escaping his mother’s dysfunction required great strength. The kind I suspect you can have only if you’re made of beautiful, indestructible stuff.

—Jennifer Nash

Jennifer Nash studies creative writing and literature at Harvard Extension School and Grub Street Creative Writing Center. She recently retired from serving as director of Harvard Business School's Business and Environment Initiative, where her research examined the role of business in the age of climate change.

For a different reading experience, The Keepthings’ stories can also be read in their entirety on Instagram @TheKeepthings.

Have a story to share? Please see the complete submission guidelines, including photo guidelines, at TheKeepthings.com.

I love this meditation on hard things.

Your dad sounds like he was a remarkable man. I love the imagery of the two of you savoring being tossed about in the cold sea, pulling yourselves out of the water by strands of sea weed and then each having a warm space on the granite rock for yourselves, a book and a book holder.