THE ARTIFICIAL LARYNX

“At the end of his life, Dad had esophageal cancer, probably related to the three packs a day of filterless French cigarettes he smoked for 30 years.”

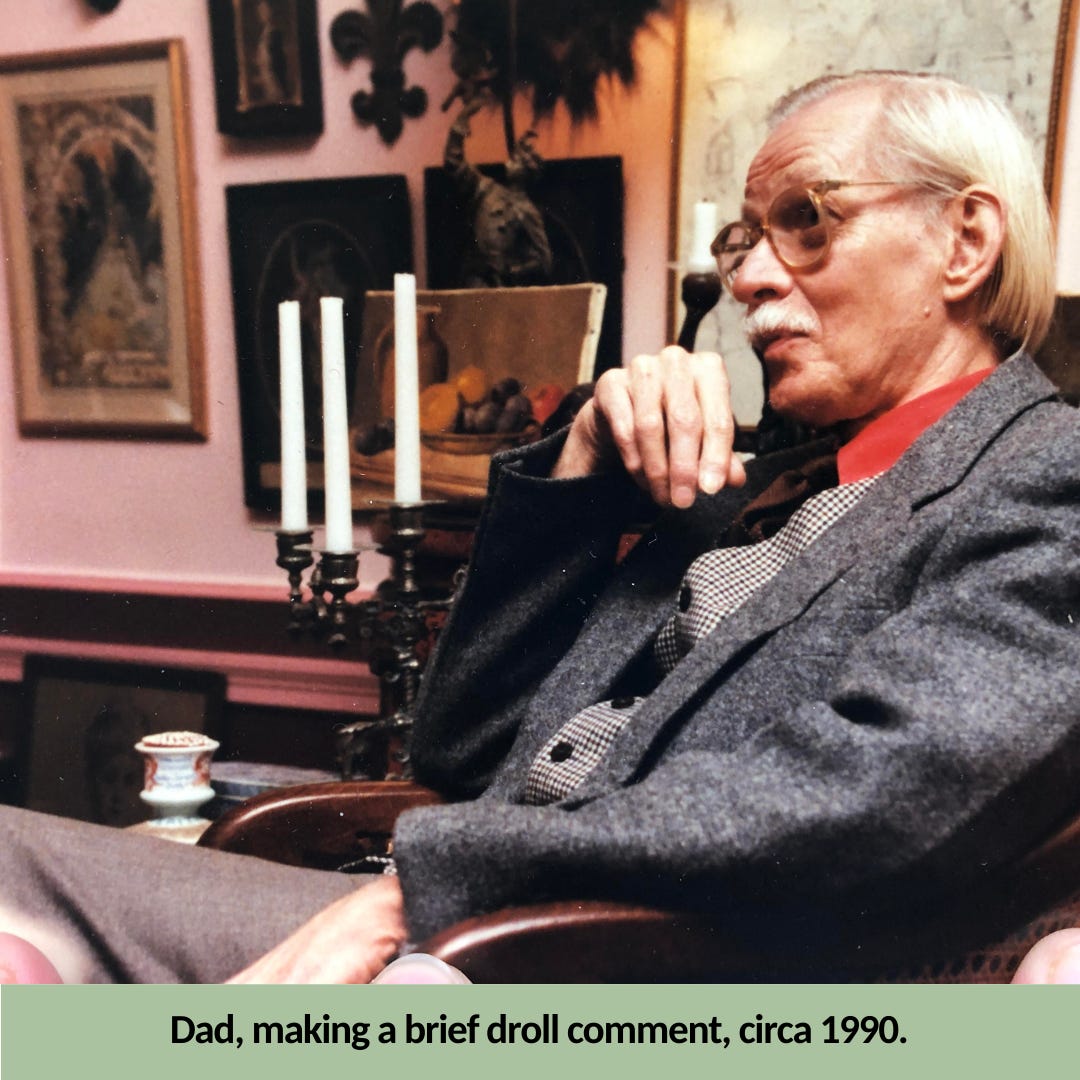

My father was a man of few words. Trained as an architect at the New Bauhaus, he latched onto the maxim “less is more” and never let it go. Unless he was reading aloud—which he did for my brother and me when we were little and he was still married to our mother—he barely spoke more than a sentence at a time.

At the end of his life, Dad had esophageal cancer, probably related to the three packs a day of filterless French cigarettes he smoked for 30 years. The night before his esophagus and larynx were surgically removed, he made an audiotape on which he recited two poems by Yeats and also narrated some memories from his childhood: climbing a tree in the backyard; a scene involving a lost shoe at a riverbank; his own father’s tendency, at family’s gatherings, to walk off and disappear. I sat with him in the hospital as he started to record. To hear him speak at such length for the first time while knowing it would be the last was devastating.

On my way out, I ran into Dad’s shrink. (We had met 15 years earlier, when my brother, my stepmother and I had been summoned to hear my father admit to us that he was an alcoholic.) “You seem upset,” said the shrink. I told him it was hard to see my father lose his voice. “Well, he never said much anyway,” he responded. I went down in the elevator, still weeping, but also thinking, “You cannot make this shit up!”

And so I’ve held onto my father’s electrolarynx. Although purchased in the 1990s, it looks like a war relic: stainless steel and sturdy plastic, with a toothed dial for volume and huge on-off buttons made of Bakelite. To use it, you held it against your throat and let it discharge a cloud of amplified noise into the chamber of your mouth, while—silently—you formed words. The top surface had to make a seal with your skin, and to avoid feedback you had to aim it just so. Dad never got the hang of it. The brief, droll comments that had been his trademark were no longer possible, and this, among other indignities of life with cancer, embittered him.

After his death, I couldn’t really bring myself to listen to the tape. For 20 years I moved the cassette from one tape player to another, and—as tape playing ceased to be a thing—into ever-deeper storage in my apartment. But when I finally felt ready to hear from Dad again, the tape was nowhere to be found. Apparently, I had thrown it out—still inserted in some obsolete player device. The word “rueful” was invented to describe how I felt. Only more so.

Early in the pandemic, my brother emailed me a large Quicktime file with the subject line: “a surprise.” Expecting a cute movie of my niece and nephew, I opened the file and heard my father’s voice. It was the audio from the missing cassette, which it turns out I had very cleverly sent my brother to digitize along with a bunch of photos and movies we decided to save after our mother’s death in 2019. Dad’s voice was just as I remembered: Midwestern, ironic, more alto than tenor…yet this teller of nostalgic tales was an unfamiliar character.

So the lost-then-found cassette is not what I keep on the shelf in my living room to remind me of the father who loved me but never said so. Instead, I display the electrolarynx, a model of minimalist design that spent its working life kissing the bristly tendons of my father’s neck—even after he had become bitter and un-kissable.

—Rachel Cline

Rachel Cline is the author of three novels, most recently The Question Authority.