I never met my great-aunt Evelyn, who died over a decade before I was born. But I’ve heard plenty! She was proudly self-reliant, married only briefly. She was confident and funny, instructing her many young nieces to call her Pretty Aunt Evelyn. She kept a bounty of jewelry in a basket in the parlor and offered sparkling items to any visitor who showed interest. And was she bold! In one well-known family photo, she’s resplendent in a hat of neon-pink poodle curls. While she wasn’t much of a housekeeper—she named her overboiled spaghetti in its runny sauce Thick and Thin—she enchanted her siblings and their families, a true free spirit.

By contrast, the women her younger brothers married—my grandmother Anna and my great-aunt Ruth—are much more understated and traditional. Growing up, I always admired their elegant homes, their tasteful dress, their impeccable manners, their excellent cooking—and the ultimate proof of their capabilities: their decades-long marriages. Anna and Ruth both pursued careers of their own in the masculinist 20th century, but also faithfully supported their husbands and raised successful Black daughters. As wives and mothers, they seemed perfect.

When I was engaged to be married, I felt more like an Evelyn than an Anna or a Ruth. At 32, I had lived alone for years, working as an attorney, and I worried I was not fundamentally wifely. (Was I already too old to learn to iron? Did I even want to?) Perhaps knowing I could use the help, the month before my wedding, my godmother hosted an event she called a “sage shower”—a tea to which the many older women of my proverbial village were asked to bring a gift and a piece of marriage or life advice. One by one, each woman presented me with her gift, speaking for a minute or two on her hopes for me.

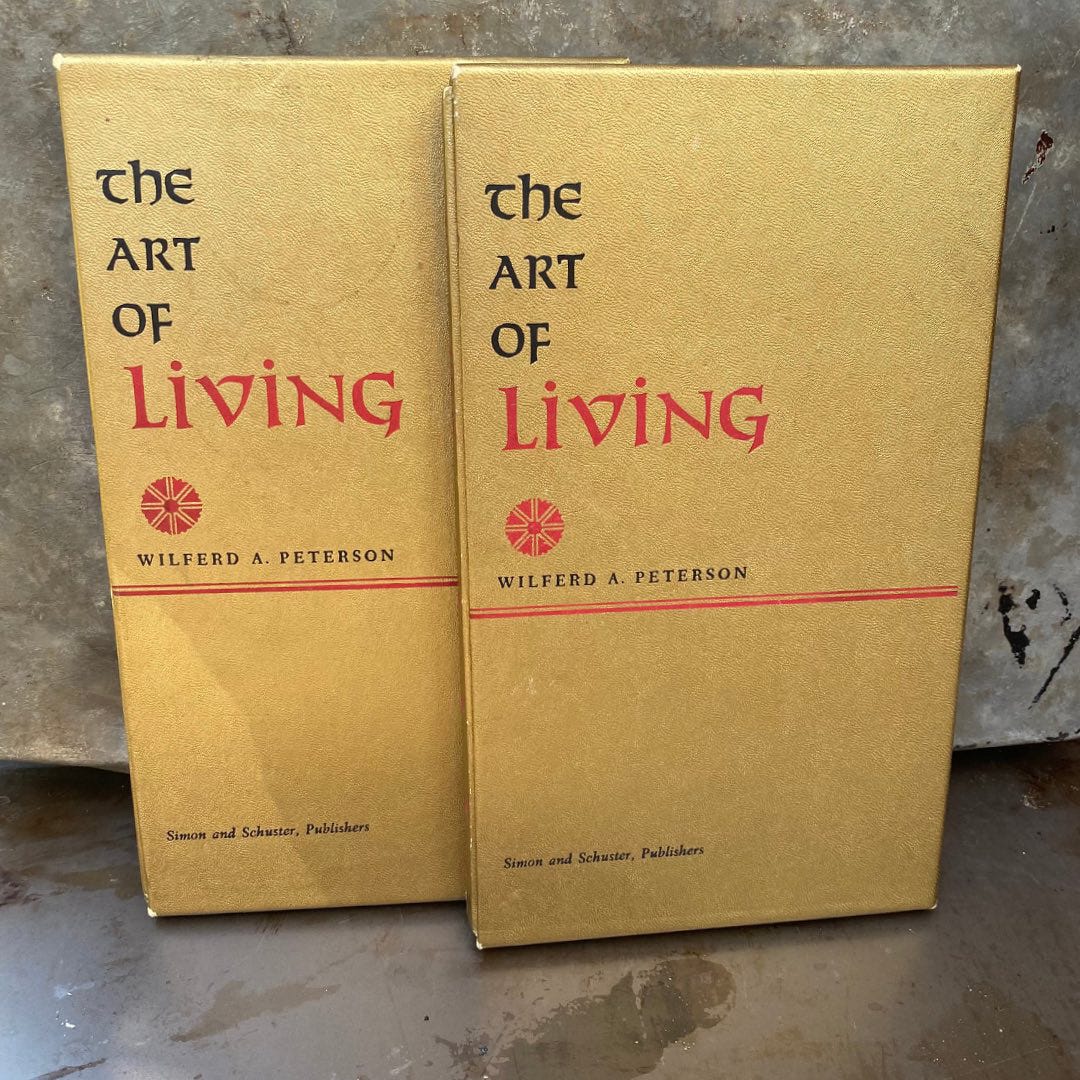

When it was my grandmother’s turn, she handed me her decades-old copy of Wilferd A. Peterson’s The Art of Living, signed and gifted to her by Aunt Evelyn at Christmas 1968. A slim, stylish book, it contains lyrical essays—“The Art of Giving,” “The Art of Traveling,” “The Art of Mastering Fear,” and so on—that inspired my grandmother enough to pass them along. A few minutes later, it was my great-aunt’s turn, and with a little smile, she rose and handed me … her own copy—also from Aunt Evelyn—of the very same book!

There were gasps and murmurs and laughter all around. I looked from Granna to Aunt Ruth, waiting for them to explain the trick, but though they talk all the time, they hadn’t planned the duplicate gifts and were as surprised as I was. To everyone in the room, it was as if we had been visited by Aunt Evelyn. Emphatically twice.

And that is how I think of it still every time I see the identical volumes side-by-side on the bookshelves I now share with my husband and three sons. Other gifts I received that day targeted the wife I was to become; the book—with meditations on everything from laughter and friendship to professional achievement—spoke to my essential personhood. Like my grandmother’s copy, Aunt Ruth’s is inscribed with Aunt Evelyn’s quirky, confident signature, dated 1968. Small notations highlight their favorite passages. The essays emphasize the grace and open-mindedness I’ve seen play out in my grandmother’s and great-aunt’s lives.

I had always imagined Aunt Evelyn too independent to be interested in the trappings of “married life.” But of course there is no hard boundary between that and any other sort of life; all lives are what we make of them, and we can—we must—define their terms with intention. (I still never iron.) Aunt Evelyn, by way of Granna and Aunt Ruth, recommends that I imbue mine with the arts of giving, of traveling, of mastering fear, and so on. And I appreciate the sage advice.