My grandfather was born in 1931 and grew up in the south of England. He was an only child, and during the Second World War his father went to prison, for a year I think, for being a conscientious objector. My grandfather and his mother were left with no income and had to rely on help from anyone who would give it, but conscientious objectors weren’t liked or respected when so many other men had gone to fight. Some days my grandfather would skip school and walk the streets by himself because he didn't want to be bullied or tormented, and if he was lucky he’d get a little food from someone who felt sorry for him.

So he had a difficult childhood and grew up to be a frustrated man. He and my grandmother married quite young; he was only 20 when my mum was born. He struggled with alcohol and was way too physical with my grandmother and ended up walking out on the whole family when Mum was about 13.

My experience of him was so different. By the time I came along, he’d remarried and moved to a valley in Wales, so we saw him only once or twice a year. The visits were difficult for my mum—a lot of old wounds—but to me he was still special. He was a biologist. He worked with blood cells, I think, in a laboratory in a hospital. When he visited, I’d come home from school and we’d sit at the kitchen table and he’d ask about my day and what I was studying and what I was reading. I was a voracious reader consuming at least a book a day. And my grandfather would read to me. He wore the soft flannel shirts that old men wear, and corduroy trousers, and he had big dark thick-rimmed glasses and a big gray beard.

I know that even in his old age, he was still kind of an angry man. But a man looking for forgiveness for the hurt he caused when my mum was growing up. He talked to her about his faith, how he believed in a God that could forgive the wrongs of the past, how he still believed in redemption.

As a boy, he probably didn’t have many toys. But in his retirement he built a big shed on the side of his house and filled it with a huge model railway. And he volunteered at a local steam railway. Every Christmas people could take the steam train up the mountain, and up at the top he was always the one dressed as Santa. When he died and his coffin—it was a wicker coffin—was lowered into the ground, his wife blew the guard’s whistle and waved the flag as if the train was leaving.

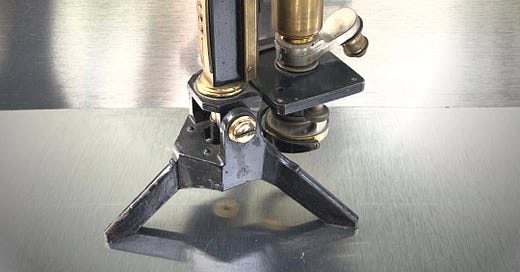

After his death his wife kept most of his things, but the microscope was offered to me. Though I’ve heard so many stories of how drunk and violent he was, to me the microscope represents the beauty of discovery and learning and ultimately healing.

When he lived in England my grandfather’s name was Brian; when he moved to Wales he changed it to Bryn to sound more Welsh. He worked hard to learn to speak Welsh, too, because he wanted to fit in. From having a dad who didn’t serve his country, and from being so poor, I think he always felt like an outsider, and I think that wasn’t easy. I sometimes wonder if the microscope might have been a way to escape. You look down through that lens and everything else falls away.

—Helen Roberts