I knew that my father was someone who held on to things (his junior-high autograph book, the sign from his grandfather’s tailor shop). I even knew he was a scrapbook-maker—I’d long had in my possession one devoted to his and my mother’s courtship days. He’d given it to her when he joined the army in 1948, then kept sending pictures for her to add to it, even though she’d broken up with him before he left. On the back of each photo is a variation of “Another souvenir for our scrapbook, darling, if you haven’t thrown it away by now.” She hadn’t. One of the final items in the book is a handwritten roster of their wedding party.

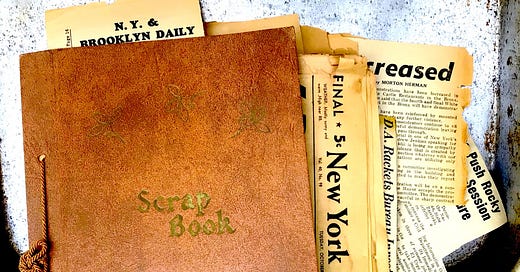

It wasn’t until after he died, in 2014, that I found this other scrapbook, wedged into a row of books shelved two-deep in the living room. It was—is—filled with newspaper clippings. Photographs my father took of fires and crime scenes, cops and apprehended criminals, car crashes and other calamities. And stories he wrote: news stories, human interest and sports stories, editorials, reviews (including one of the Mona Lisa, which visited the Metropolitan Museum of Art for three weeks in 1963—Dad thought it was good). All the clippings are from the early ’60s, when New York was a city with many daily papers.

Perhaps that’s why he was able to get this sort of work (that, and his sheer determination, and how hard he was willing to work for almost no money). He was a high-school dropout. His parents owned a hardware store where in his spare time as a kid he’d worked, resentfully, for years, and where he was expected to go full-time once he turned 18. He had other plans. In the ’50s he started selling the photos he got by chasing sirens. Later, when we were out somewhere together as a family, we'd all go to the fire, to the fresh murder scene. “Stay in the car,” he’d say, and we would, while he got out to get the pictures and the story.

But he couldn’t earn a living at it. I can’t remember a time when he wasn’t also selling life insurance. All the papers in the scrapbook—the New York and Brooklyn Daily, the Brooklyn Eagle, the Daily Mirror, and so on—shut down for good in 1963. He moved on to other papers—the New York Journal-American, the New York Knickerbocker—but by 1969, when I was 14, they were gone too.

And so was I, sort of. Until I became a teenager, I’d been his sidekick and best friend. While my brother and mother stayed home, he took me with him on assignment. I rode in a police helicopter (it had no doors; I was terrified). When I was 11, I accompanied him as he covered one of the glamorous Mayor Lindsay’s famous neighborhood walks (the mayor bought me a Charlotte Russe, my favorite pastry). At home, I would sit and watch him shave while we talked. He taught me to draw—taught me about perspective (where did he learn about it, I wonder). And then overnight I suddenly I had no use for him.

I always assumed that our years-long period of estrangement was the result of my miserable adolescence. Certainly he was baffled about how to relate to me once I no longer hung on his every word, once I began alternating between disdaining and ignoring him. But I think now that the loss of his life in newspapers must have been part of his anger and sadness too. He must have felt he’d lost the two parts of his life he loved most.

My father was in his early 30s when he put the scrapbook together—half the age I am now. At one time each clipping must have been carefully glued down, but although they’re still in there, loose, the pages are all empty.

—Michelle Herman

Michelle Herman’s ninth book is the novel Close-Up. She dispenses parenting advice every Sunday on Slate.