MOM'S LIPSTICK

“She wasn’t a hoarder, but she was part magpie. She loved bringing shiny objects back to her nest.”

Mom loved to primp. After she died, when my sister-in-law and I cleared out the bathroom, her shampoos and creams and lotions and cosmetics filled a 42-gallon trash bag. Dad hovered in the corner, wringing his hands with anxiety and grief; we needed to be quick. I was robotically chucking things when I saw the vintage lipstick. The golden ridged-metal casing was scratched, but the tube still glinted in the light.

Mom had a Ph.D. in early-childhood education and worked in the public schools. (Dad had a Ph.D. too; he was a professor. People would call asking for Dr. Ferguson and I’d say, “Which one?” I loved how the men would stammer.) She wasn’t a hoarder, but she was part magpie. She loved bringing shiny objects back to her nest. I’m part magpie too. When I found that golden tube of lipstick, I stashed it in my bra, as I’d done with cash tips when I waited tables.

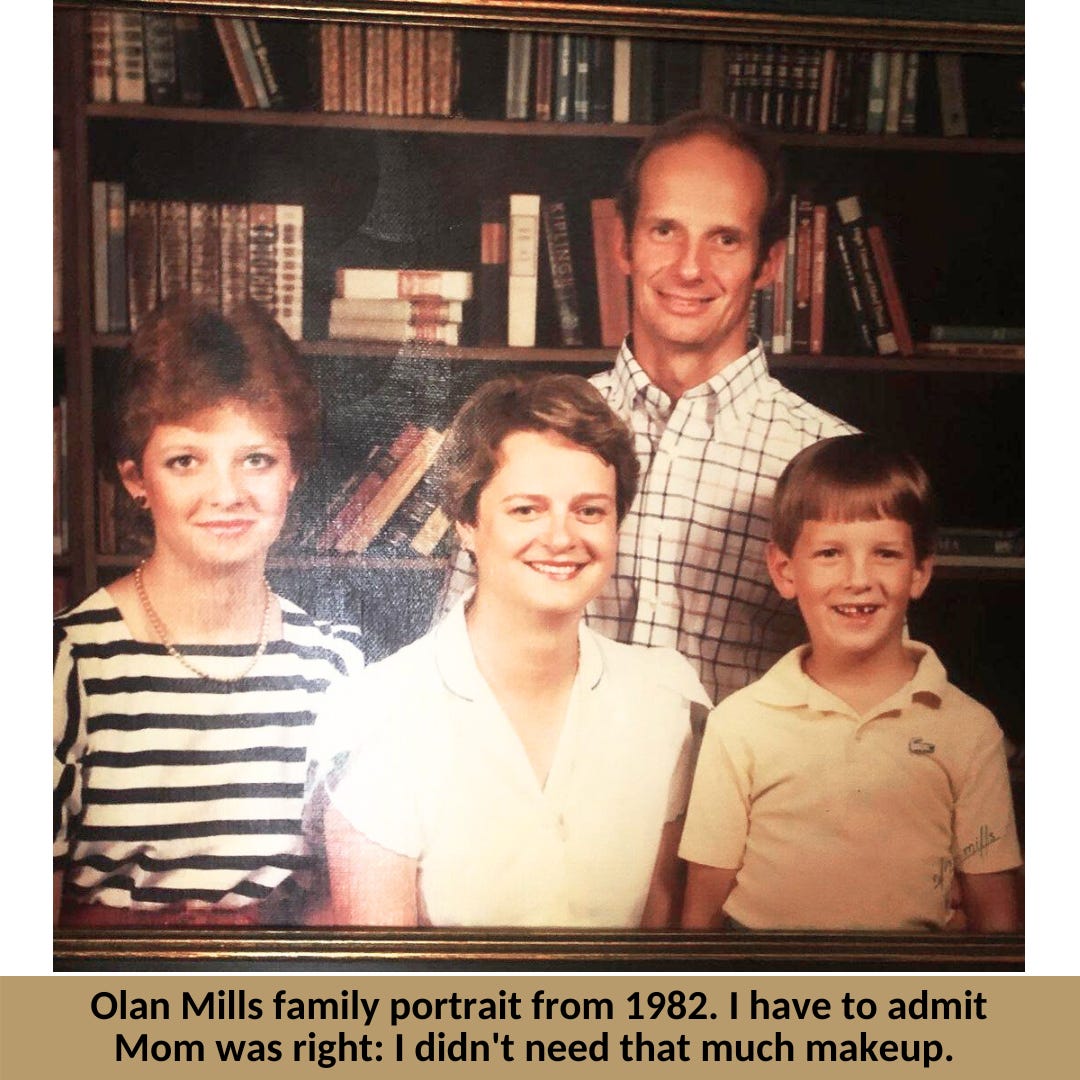

Later, back in my nest, I examined my find, turning it over under a lamp: Estée Lauder All-Day Rich & Rosy (A-19). The pop of the cover, the waxy floral scent—and just like that it’s 1981 and I’m 13, getting ready for school, Clairol hot rollers heating, contemplating the Maybelline Kissing Potions I’ve swiped from the drugstore but knowing it’s glamour I crave, Alexis-Colby-Carrington-from-Dynasty-level glamour, classy-business-lady-from-a-Judith-Krantz-novel-level glamour. Estee Lauder—department-store makeup—is that level glamour. Which is why, whenever I can, I sneak into Mom’s bathroom, covet the lipstick and dream.

I don’t apply it, of course. Mom is strict—Austro-Hungarian-Catholic-ancestry strict—and I’ve already broken her amethyst earring and stunk up her silvery cowl neck with preteen B.O. Transgression would mean interrogation. I’d be cornered—What is wrong with you?—until I broke down and confessed. Still. I need that lipstick. And so one morning, while she’s eating, I sneak into Mom’s bathroom, heart thudding, twist the base all the way, really going for it, yeah!—and the whole cylinder of pink breaks off and falls into the sink. Plop. Panicked, I stick it back on and race to scrub away the pink stain, but the lipstick is dented. Ruined.

Days pass, doom gripping my chest as I await the inquisition. A few nights later at dinner, Dad is telling one of his long stories when Mom looks right at me and sighs the deepest of sighs. She knows. Of course she knows. But in that sigh I hear that she has decided to let this one go. Maybe she’s exhausted from work. Maybe she’s exhausted from me. (I am definitely exhausted from being made to feel like a terrible person for stuff other moms don’t care about. And from wishing she’d like that I want to use her things. Even if I do ruin them.) Whatever the reason, phew, thank you, I’ll take it.

And now, 42 years later, here was the forbidden lipstick, one of the few things I kept from that post-death bathroom purge. Bathrooms, it turns out, reveal a person’s greatest frailties—a truth that hit me as I threw out Mom’s Rogaine. She’d always had a crown of thick lustrous hair. The admission of lost beauty must have pained her.

My mother died ten days after her leukemia diagnosis. On every one of those days, she made my father promise not to have a funeral. She refused to see her friends. Refused to see her granddaughtersand daughter-in-law. Μy brother had to force his way in. I was going to force my way in but didn’t board the plane in time. I think Mom was mortified to die, hated the idea of not looking her best. For her final exhale, she waited until Dad stepped out of the room. Afterward, the hospice worker told him this wasn’t uncommon. “Ladies have their pride, you know,” she said.

—Kelly K. Ferguson

Kelly K. Ferguson is the author of My Life as Laura Ingalls Wilder (Press 53). In the past ten years she has moved from southern Louisiana to southern Ohio to southern Louisiana to southern Utah to southern Ohio, where she teaches at Ohio University.