FOTI'S WILD BOAR TUSKS

“They all made it a point to look after me, but Foti…roped me into his adventures.”

When I was 27 I moved to the mountaintop Greek village where my father was born to oversee the rebuilding of my grandparents’ house, which had fallen into ruin decades earlier in the aftermath of the Greek Civil War. I was working on a travel memoir and taking a break from the career in magazine journalism I’d thrown myself into four days after graduating from college, back when I was worried that I’d float off into oblivion if I weren’t attached to an institution or daily routine. In hindsight, I think Greece was probably my solution to a quarter-life crisis, diving into my past to figure out my future.

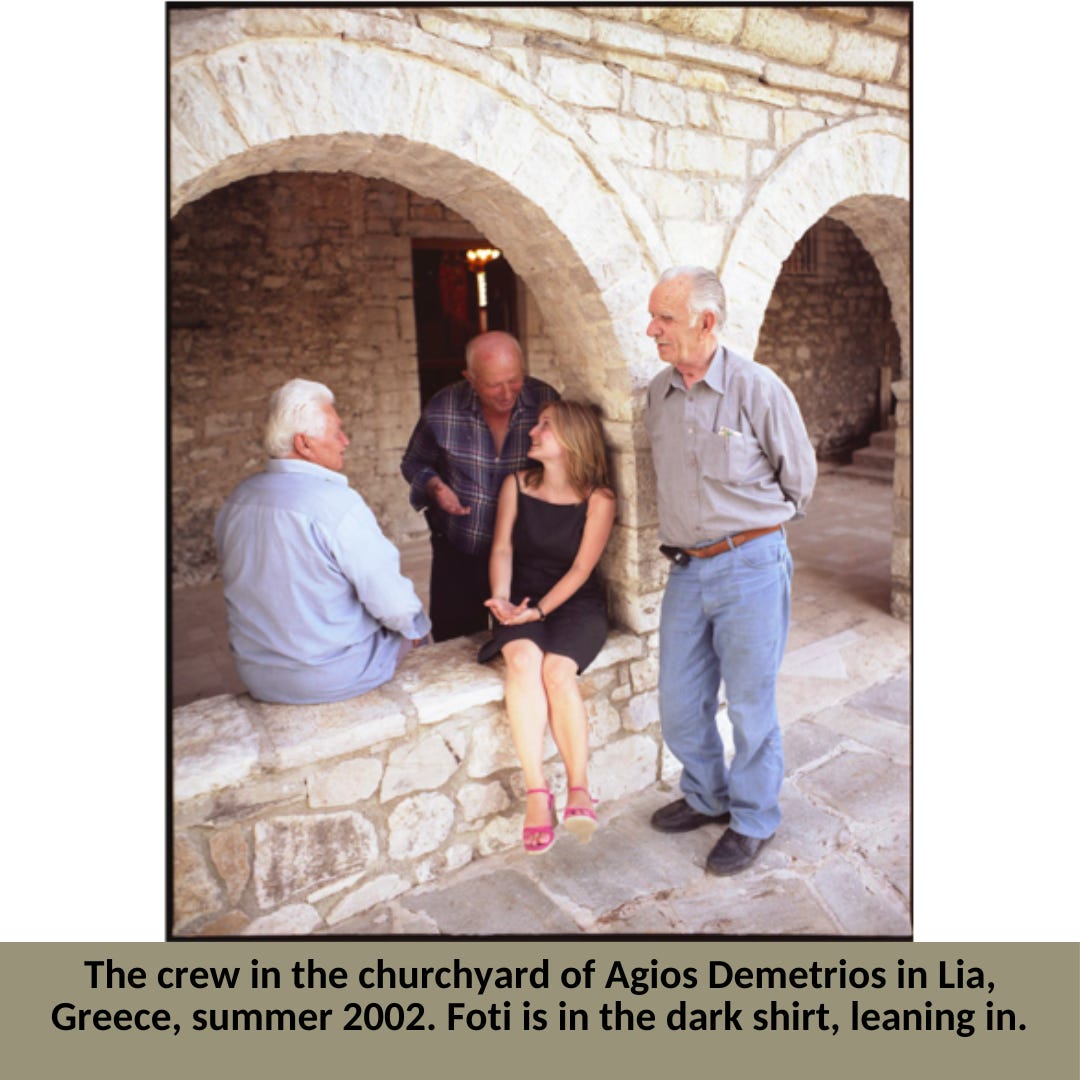

Foti was my uncle’s brother-in-law, a widower who lived with his large hunting dogs on top of a peak overlooking the village. All the young people had moved to cities to work, so the village’s entire year-round population was maybe 100 or so senior citizens. They all made it a point to look after me, but Foti actually hung out with me and roped me into his adventures. I’d go to dinner with him and his buddies at a grill three villages over with rhyming couplets painted on the wall and local wine that came out of a tap from what looked like a water cooler.

Foti called me when the shepherds drove their sheep from the mountaintop pastures to the lowland in October, so I could watch the migration. He showed me the waterfalls that pour from the mountain after the winter rains. He got a buddy with a truck to drive us off-road to a thousand-year-old monastery with monsters and dragons painted on its ceiling. As a boy, he’d spent a night on the monastery’s grounds when, after the Civil War, the retreating Communist army forced the village’s women and children over the border into Albania.

Foti’s life hadn’t been easy. But now he was living the dream, retired and back in his ancestral village after years spent working in, then owning, pizza places in the U.S. He tended his chickens and his garden, went hunting with his friends in season. Once, they shot a wild boar. A month or so later, he gave me its tusks, linked with a silver joint and a clasp so you could string a ribbon through them; the hunters hung these trophies from the rearview mirrors in their cars.

I don’t hunt and I’ve never owned a car, so I strung the tusks on a chain and wore it as a necklace, the most badass piece of jewelry in my decidedly un-badass wardrobe. After my grandparents’ house was rebuilt and I returned to New York, I wore the necklace when I gave talks about my travel memoir in church halls full of other Greeks who dreamed of returning home.

Foti died unexpectedly two years after I left the village. In my book talks, I described him as a “self-appointed uncle.” I see now that I was wrong. He was my friend, the first friend I had who wasn’t my age and at the same life stage I was. And I think he’s the reason I now have friends who are younger and older, who’ve had sorrows and joys and adventures I’ve never imagined, and who enrich my life by sharing them with me.