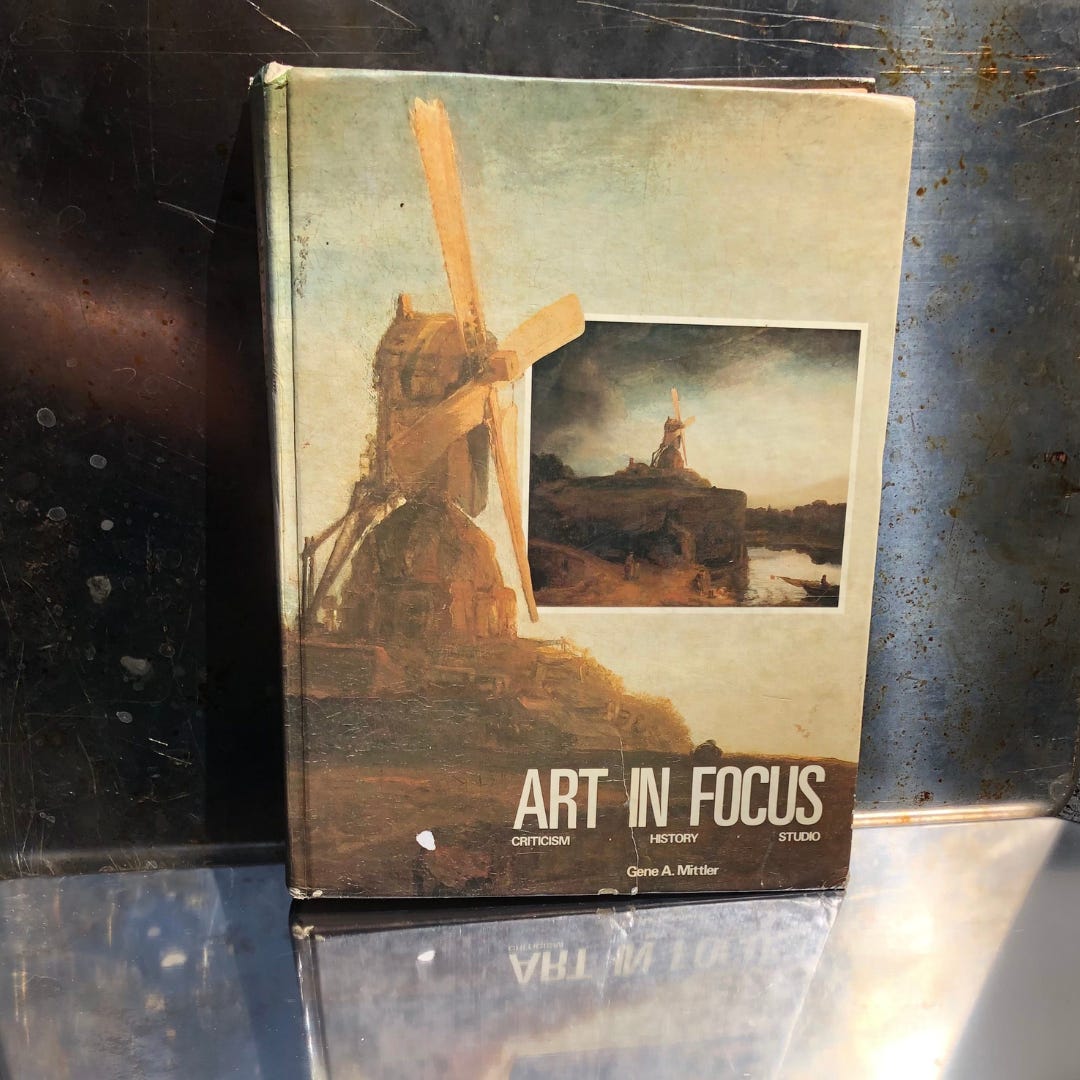

ART IN FOCUS

“…why would he think I’d want some old high-school textbook?”

My graduation party had just ended. I stood in my mother’s kitchen doorway, counting down the hours until I left home for college in Louisville, Kentucky. At eighteen, I had eyes for nothing but a future that lay 600 miles away.

My brother Joe walked up behind me and tapped my shoulder. Even though he was only sixteen, he towered above me. Yet when he tapped me again, it was like he’d grown small. He beckoned me to the bedroom he’d shared with my other brother, his twin, before they moved in with our father. Touching the wall, I thought of all the bands the three of us had listened to in that room. Ozzy Osbourne. Anthrax. Metallica. A single bed and dresser had been set up after they left.

“Here.” The space was so empty, Joe’s voice echoed. He looked away as he dropped Art in Focus and a TI-81 graphing calculator into my hands. He claimed the calculator had been lying in an empty hallway. Art in Focus, he’d stolen from our high school’s art department.

These were two of only a handful of gifts Joe had given me over the course of our lives. He knew I couldn’t afford the hundred-dollar graphing calculator required for my upcoming calculus class. But why would he think I’d want some old high-school textbook?

He pointed to Art in Focus and said, “Open it.”

I did. In the “Property Of” grid stamped on the book’s inside cover was my name, where I’d dutifully written it in when I took art history in the fall. Joe had taken the same class in spring.

“We had the same fucking book! You believe that shit?” He ran his finger over the white space where his own name should have appeared.

I chewed the inside of my cheek, unsure whether to accept stolen goods. Then he clasped his hands over mine. “Now you can take part of me to college.”

Later that night, I tucked the textbook and calculator into my suitcase. All freshman year, I carried them in my backpack, comforted by the weight of their presence—his presence—especially on days when the future didn’t live up to my dreams.

In an art class, I learned that white space is also called negative space. It’s an essential part of a composition that often amplifies the subject. But sometimes negative space becomes the composition’s subject.

Joe visited Louisville twice before he ended his life. On both visits, I planned to have him fill the “Property Of” blank with his signature. But fun times always eclipsed that task. So now every time I touch the book, I open the front cover and swipe my finger across the blank line that he once touched.

—Lisa Cooper Ellison

Lisa Cooper Ellison is a writer, speaker and coach whose work has been published in Brevity, HuffPost and Kenyon Review online, among others. She recently completed a memoir, Please Stage Dive Carefully: A Memoir of Heavy Metal, Healing, and Hope.

This is so moving, Lisa ❤️

Books hold so much more than words