ALEX'S VICTORINOX

“For Alex, food was the engine of love. This knife was his first financial splurge and became his prized possession.”

When we signed the lease on our first and only flat—Windsor, England, August 2012—I was 23 and Alex was 24. I was from L.A., he was an Englishman, and we’d met as students at Oxford. Though we’d shared a tiny dorm room for two years, moving into a larger space somehow brought us closer. Alex’s keen mind and cool remove disguised a shy, affectionate nature. At home, he belted Anglican hymns in the shower and traded his contacts for the smudged, crooked specs he was too vain to wear in public. He left behind the grace he displayed on the cricket pitch and became a charming klutz.

In that flat I learned that for Alex, food was the engine of love. This Victorinox knife was his first financial splurge and became his prized possession. He sharpened it on Sundays with a whetstone and steel until the slightest pressure sent it tearing through paper. He used it to teach me how to make a proper Sunday roast: spatchcock the pheasant, julienne the parsnips before coating them in honey, slice the potatoes into thin half-moons to be shingled in a baking dish. We’d work side by side until all was ready for the oven, then retire to a scalding bath, tangling our legs, pruning our fingers, pinking our toes. By dinnertime, we were boneless.

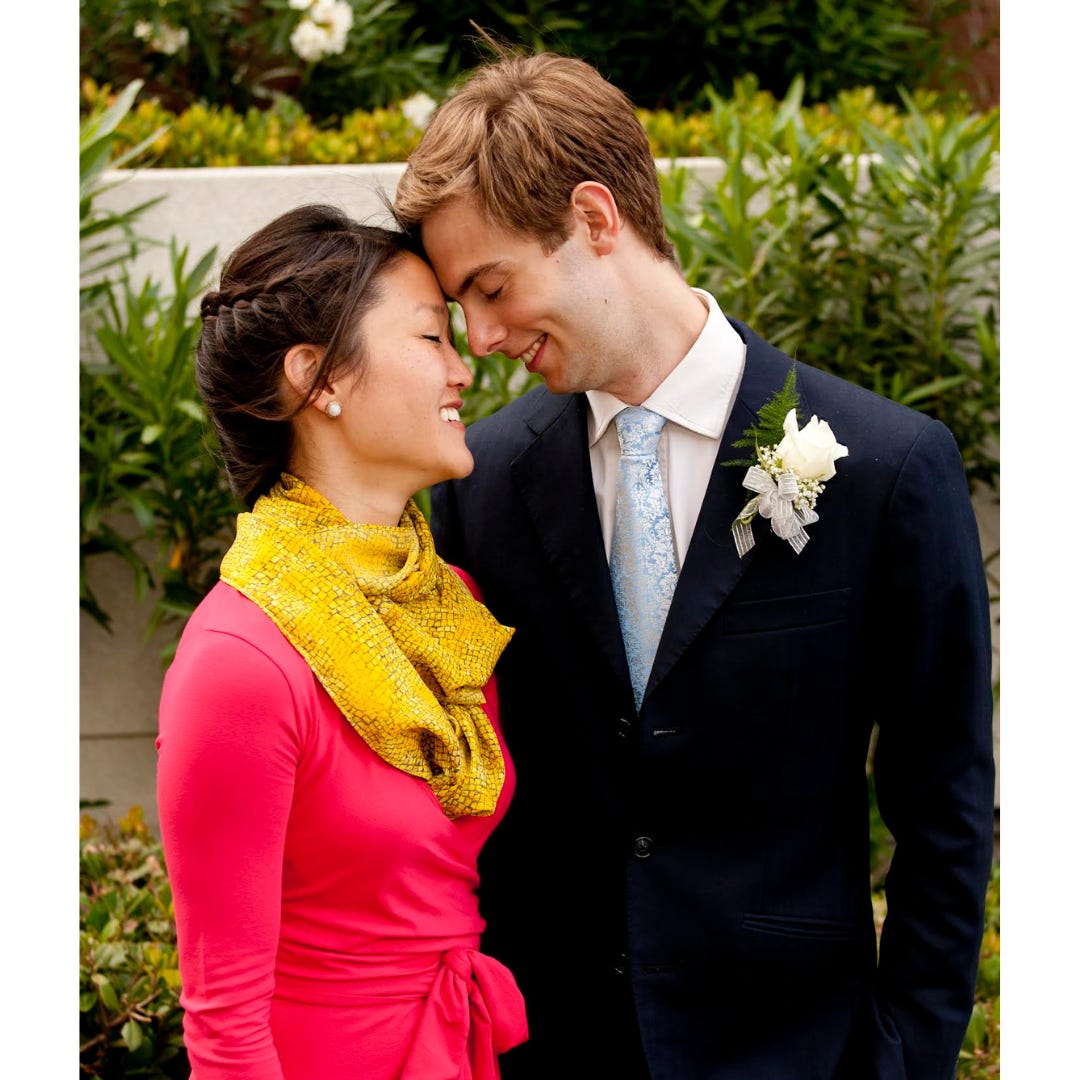

We were “content just to exist beautifully,” like Bertie Wooster in Alex’s P.G. Wodehouse books. In our Windsor sanctum, we beheld our gorgeous horizon: marriage, a mortgage, kids one day. I knew my family would adore Alex, and they did. In 2013, we flew to L.A. twice: in May for my sister’s wedding, and again in December to stay with my parents. My father and Alex liked to talk Top Gear, so as a gift Dad bought him a racecar-driving lesson, complete with a smooth white helmet like the Stig’s. No one foresaw that during the lesson Alex would crash. Broken neck, bleeding brain, instant coma.

That night, instead of curling up alongside Alex as I’d always done, I lay numbly on a cot in a corner of his hospital room. The left side of his skull had been cut out to make space for the swelling. The nurses replaced IV bags, packed his body in ice and untaped his eyelids to measure his pupils’ diameter—4mm, 5mm, so close to death. Soon the right side of his skull would be cut out as well. I’d spend the next four months at his bedside, expecting some cosmic needle to tip one way or the other. But in April 2014, the neurosurgeon declared no prognosis—words that didn’t clarify, only confused.

As Alex’s family flew him to England, I went back alone to Windsor. I swept three years’ worth of trinkets and letters into my suitcase. I shipped Alex’s books, bicycle, computer and clothes to his parents in case he ever wakened enough to want them. But his Victorinox, I kept for myself. I can’t say I did so out of sentiment or even nostalgia—all I felt was tired. I’d lost interest in food. I’d lost my sense of taste and smell. The galley kitchen had gone sterile, the porcelain tub hollow and cold. I emptied the flat and locked it for the last time. So long, Sunday roast. So long, lemongrass bathwater. Pruned fingers, pinked toes, so long.

I moved in with a friend, returned to work and visited Alex in his new hospital weekly, then monthly. The shelves in his room were lined with old companions: the stuffed lions, tigers and leopards that had prowled the curtain rail above his boyhood bed. I reported on the friends who’d moved, changed jobs, gotten engaged. I read aloud his favorite fantasy book, Guards! Guards!, by Terry Pratchett, struck by the poignancy of its first lines: “This is where the dragons went. They lie… Not dead, not asleep. Not waiting, because waiting implies expectation. Possibly the word we’re looking for here is…dormant.”

After a year of no change, I returned to the U.S. Until Covid, I visited Alex annually. It was a long process, leaving that life. I was still grieving when, in 2016, I met the man I’d marry, still grieving as I fell in love. Wedding, first home, child: each milestone inlaid with images of Alex, vacant and fed through a tube. My husband and I visited him in 2023. And in 2024—nearly eleven years after his crash—we attended his funeral. Now, each day, his knife makes its circuit from drawer to cutting board to drying rack. My husband sharpens it regularly. When he does, I can hear Alex’s voice: “Good things last forever, if you care for them.”

—Jaimie Li

Jaimie Li received a bachelor’s degree in jurisprudence from Oxford University in 2011, and an MFA in creative writing from Goddard College in 2022. She teaches workshops at Hugo House in Seattle and is working on a memoir.

For a different reading experience, The Keepthings’ stories can also be read in their entirety on Instagram @TheKeepthings.

Have a story to share? See the complete submission guidelines, including photo guidelines, at TheKeepthings.com.

This left me aching at the loss of someone I do not even know. The tenderness in every word and action.

Such a heart-rending beautifully written essay